Article by Janet Macunovich

and photos by Steven Nikkila

Sometimes while gardening, sinking my fingers and soul into the earth, I forget where I am. Entranced by a boundless web of life anchored to the plants in my hands, my own boundaries move outward and I float free in the universe.

Until my work takes me up to the edge, that frustrating place where my property butts up to a neighbor’s. How stifling to the artistic gardener, to be hemmed in with such unequivocal straight lines. So tough to bring our green, growing stuff to a graceful end at that all too rigid but oh-so-necessary political boundary.

Perhaps the toughest kind of line is the edge of a small property, a city lot. Already too confining for some gardeners, that space seems to shrink further when filled with people and pets, outlined with fences and weighted with public sidewalks.

In front, the property line slices through and lays claim to what appears to be a sliver of the neighbor’s lawn. A non-gardener may cede that land to the lawn-owner, but the green thumb, already chafing about lost ground in other areas, sees it as a strip garden marooned on the far side of the driveway. Adversity being the mother of invention, the garden grows from there.

A conventional solution

Maintaining dominion over that strip is simplicity itself—draw a straight line and plant. Hedges are conventional, safe plantings for such a spot. Or are they?

Hedge trimming is often the rub. How to keep those shrubs neatly shaped when access to their far side requires crossing the line? If each neighbor prunes his or her own side, timing and technique become issues. Through an open window one neighbor might hear, “I wish the Simons would trim that hedge, it looks so scraggly on their side!” Of course the Simons will have their rebuttal, muttered or perhaps stage-whispered over the rattle of pruning tools: “Hmph! We didn’t plant it, we didn’t get a say in what kind of hedge it would be, but we have to prune it!”

Even with synchronized pruning, uniformity of maintenance may become an issue. “Look at the weeds coming through the hedge from their side!” “Wouldn’t it be nice if they would mulch their side too, and use the same mulch we do?” “Couldn’t we continue the Christmas lights over on that side?”

The perfect hedge

Sometimes neighbors agree in advance to plant or replace a hedge, decide together on the species of shrub to be used, even splitting the cost. Such jointly-owned hedges often straddle the lot line. “True enlightenment,” one might think.

Only if people stayed planted as long as shrubs do. Our roots have atrophied, though. Homes change hands far more frequently than they did when hedges were king. Hedge care falters in the transition. Ownership of boundary plants becomes fuzzier with each new tenant. Hedge co-owners sometimes find themselves suddenly hedgeless, victims of the neighbor’s landscape renovation scheme—a neighbor who did not know he or she was only part owner of the plants.

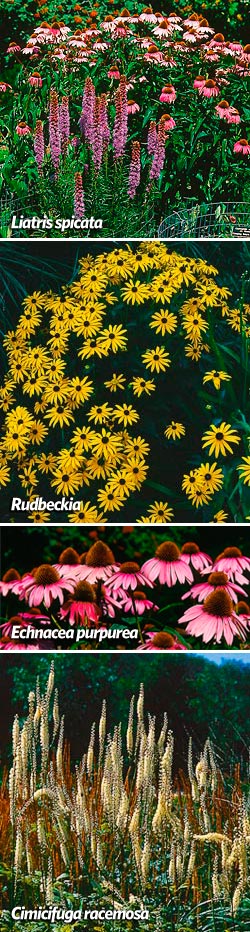

In recognition of all that can go wrong, we ought to plant narrow strip edges with a shorter turnover in mind. Daylilies, peonies, black-eyed Susans, and sedum ‘Autumn Joy’ make excellent short hedges. Individual plants in the hedge are much more portable than shrubs, can be cut to the ground without harm when home maintenance work demands a clear path, can recover in a year if damaged by a new driver’s wayward steering, and can provide far more color than shrubs which lose some flowering wood at each trimming.

For more height in a herbaceous hedge, consider using ornamental grasses, vines on a trellis, even asparagus. Although these selections may fall a few months short of a full year presence, they make up for that failing in speed of establishment. In just two years, a row of zebra grass (Miscanthus sinensis ‘Zebrinus’) can make a solid six-foot wall. The wall disappears from April 1 until June 1 as the plants are cut to the ground and bounce back, but it’s there in full density during the height of the summer barbecue season and the windiest winter storm.

Creative curves

What about the gardener’s need for artistic expression? He who loves curves can become frustrated with long, narrow spaces that seem to demand long, straight lines of plants.

However, a straight line of plants need not have straight sides or tops. It can be tall at one end, short in the middle, medium height at the far end. It can consist of several types of plants of naturally varying widths and heights or a single type pruned to create a curvaceous top or side.

Try it—draw a narrow rectangle. Now draw a wavy line within the rectangle, along its long axis. To plant the line, stagger plants to trace the crests and troughs of those waves. As you maintain the bed, remember to preserve open space between the straight edge of the bed and the plants. This may mean strict use of pruning shears or careful selection and thinning of plants.

Window walls

Deviating from a straight line can have advantages in neighborliness. No one likes to feel that he or she has been walled out of an area. One way to break up a forbidding wall is to interrupt it with an inviting window or door.

Think it through before making the breach and it will be inviting without being a blanket invitation to peep or enter without knocking. Place the opening carefully and you can offer a pretty vignette yet preserve privacy. Set the door in a logical place and neighbors—even children—will use it. If you don’t want it used too freely, sink a pair of posts and hang a gate.

Invisible lines

Sometimes although we want to garden along the edge we don’t want a line at all but some less divisive visual flow from one property to the next. That’s the place to step back and take a wider view. Design the edge to continue an existing bed on the neighbor’s lot, or one on your lawn across the driveway. Even if the outlines of your edge bed and the other don’t join directly, you’ll achieve a unified effect if it appears the two beds’ edges would flow into one other if extended.

Another way of connecting isolated beds is by planting them to repeat species, color, texture, shape or alignment of plants in other areas. The link can be strengthened if the same or related non-plant items appear prominently in the beds. If an abstract rusted metal sculpture with a southwestern desert feel anchors one bed, repeat that theme in the next.

Give and take

Sometimes house placement and fencing isolate an area from foundation to lot line along one side of the house. The area may be accessible to its owner only by a long walk around and across the front yard, and then can be viewed straight on only from the neighbor’s driveway or patio. Some people leave such an area in lawn for ease in care and neatness of appearance. Some garden the space for the fun of gardening and the pleasure it gives the neighbor. Others cede care of the area to the neighbor if that person has both the best view of the bed and a desire for more gardening space.

If you’ve granted gardening rights to the neighbor on such a space, ask for compensating land elsewhere along your shared line. Who knows, maybe that neighbor is fed up with gardening the strip along the driveway and will let you take it over to expand your lawn!

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of the books “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet on her website www.gardenatoz.com.