by George Papadelis

It turns out that one of Michigan’s most common roadside “weeds” is actually an outstanding perennial for our Michigan gardens. The brilliant orange flowers of butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) can be seen blooming profusely in June and July in some of the most unfriendly sites one can imagine. Open meadows, steep slopes, and grassy fields can provide its only two cultural requirements: full sun and dry, well-drained soil.

Butterfly weed was given its common name for appropriate reasons. When in bloom, its flowers seem to attract butterflies from miles away. Monarchs are perhaps the best-known visitors to members of the milkweed family (to which butterfly weed belongs), but many other species dine on their nectar as well. Painted ladies, swallowtails, and others find it irresistible. All milkweeds are suitable lures for butterflies, so select the variety that best suits your tastes.

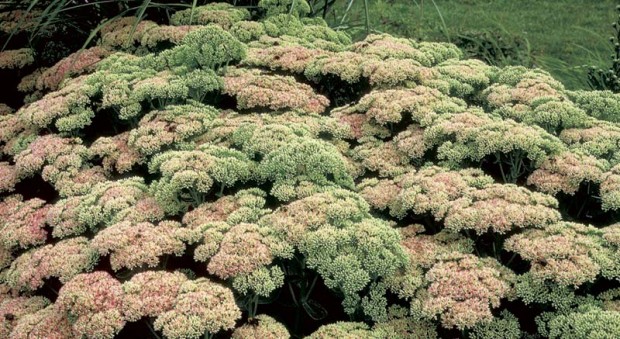

Butterfly weed, with its flat clusters of small orange flowers, is actually one of the few perennials available in orange. Its perennial companions in this narrow color range include poppies, red hot poker, daylilies, lilies, and crocosmia. Butterfly weed is also available in some different hues. The variety ‘Gay Butterflies’ offers a mixture that includes orange, yellow, and red. An all-yellow variety exists (‘Hello Yellow’), but is often difficult to find.

More milkweeds

Butterfly weed has another North American relative with the less flattering common name of swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). The common name comes from the milky sap produced from broken stems or leaves. Swamp milkweed varieties offer flowers similar to butterfly weed, but in two different colors. One called ‘Cinderella’ produces larger, rosy-pink blossoms on more compact flower heads. ‘Ice Ballet’ yields all white flowers that create the perfect backdrop for brightly-colored butterfly visitors. Both will grow about 3 to 4 feet tall.

Tropical milkweeed (Asclepias curassavica) is another popular species of asclepias. This annual form can begin blooming as early as May when cultivated in greenhouse conditions. It produces extra vibrant orange and red bicolor blooms from spring until fall. Besides a sure death every fall, it offers everything available from the perennial forms, but boasts a longer bloom time. Like its longer-lived counterpart, this annual can also have a place in the perennial border.

How to grow butterfly weed

Butterfly weed is difficult to propagate. Seeds are tough to germinate and it also has a taproot that makes it almost impossible to divide. Even transplanting can be problematic. Garden centers are the most reliable source to obtain young starter plants. Once established in well-drained soil, butterfly weed can flourish for several years. Competition from grass and weeds is rarely a factor, but tree roots may pose a problem. Heavy, moist soil (which often occurs in southeastern Michigan’s clay) must be amended with coarse sand, compost, and/or pine bark to improve drainage. Otherwise, good garden soil is all that’s required for this two foot tall, native perennial to produce its flowers. In more harsh environments, evergreen boughs placed directly on the plants for winter protection would certainly be worthwhile. Be patient in the spring, since the leaves of butterfly weed, like several other perennials, are very late to emerge. Gardeners often mistake plants as dead and then discard them before new growth is able to develop.

Besides attracting butterflies and adding some color to your borders, all varieties make excellent cut flowers. Blooms allowed to remain on the plant give way to narrow seedpods, which provide an additional dimension to the plant. These can be harvested before they split open and dried as ornamental seedpods, adding a unique element to any flower arrangement.

Butterfly weed is a Michigan native that is both versatile and rewarding for the true Michigan gardener. Whether butterfly weed is in your yard, in a vase, or on the menu for a passing butterfly, it is one weed you’ll never want to pull out.

Butterfly weed

Botanical name: Asclepias tuberosa (as-KLEE-pee-as)

Plant type: Perennial

Plant size: 2-3 feet tall; 2 feet wide

Hardiness: Zone 4

Flower color: Orange, orange/yellow/red, pink, white

Flower size: 1/4 inch wide, on clusters

Bloom period: Midsummer

Leaf color: Green

Leaf size: 4-6 inches long, lance-shaped

Light: Full sun

Soil: Dry, well-drained for butterfly weed (A. tuberosa). As its common name indicates, swamp milkweed (A. incarnata) prefers more moisture.

Uses: Perennial garden, meadow, roadside, cut and dried flower arrangements.

Remarks: Native to Michigan. Attracts butterflies. Very slow to emerge in spring, so be careful to allow new growth to appear. Has a taproot, which makes division difficult.

George Papadelis is the owner of Telly’s Greenhouse in Troy and Shelby Township, MI.

Related: How to transplant butterfly bush