These handy lists will help you select excellent shrubs and place them in the right spots

Shrubs play a major role in landscaping, as we create a hedge here and cover the ground there, there, develop a backdrop in one spot and a pivotal year-round focal point in another. As I design, each shrubby player begins as a set of desirable characteristics, sans name. My rough sketch might have a note like this next to a prominent circle: “Eight feet tall, rounded in outline, winter interest, and color in one or more seasons.” Then, auditions begin and I select possibilities, working from a list of about 200 choice shrubs I’ve come to know how to use. Once the field is narrowed to just 2 or 3 candidates for each role, I consider how those in that smaller group will play as a team and perform in the given environment. In the end I have a line-up in which every plant can shine.

I expect that all my life I will keep trying shrubs I haven’t grown before, so this list will change in time. Certainly there are some that will take the places of my current favorites.

For instance, there’s cinnamon clethra (Clethra acuminata), a tree-like shrub I want to plant and watch in various sites to see for myself if its bark is always so gorgeous as I’ve seen at botanical gardens. Its flowers aren’t nearly so fragrant as those of its little cousin now on my list, but a winter’s worth of pretty bark could trump summer scent.

There are dozens of St. John’s worts (Hypericum) to try too. If it turns out that golden St. John’s wort (H. frondosum) keeps its blue-green character and bigger, brighter yellow flowers even once it’s old, in all kinds of sites, it may replace Kalm’s St. John’s wort on my drawing board.

And there are so many natives still being selected and developed. I hope to try some selections of leadplant (Amorpha canescens), with gray foliage and violet flowers in summer. My bet is that it will be a better groundcover for the Midwest than creeping cotoneaster.

Oh, for a dozen lifetimes so I could try and report on them all—bush whacky!

Big, multi-season beauties

Chinese spicebush (Lindera angustifolia)

10- to 12-foot, upright shrub with fragrant foliage, twigs, and seeds. It opens small yellow flowers in abundance in April. The foliage glows a pretty orange in fall but then fades to parchment and hangs on over winter in zone 5. It can be evergreen in milder zones. So the plant is a natural as a four-season screen. Part shade or full sun.

Chokeberry (Aronia arbutifolia)

6- to 10-foot, upright shrub. Can be a specimen, but over time can sucker to form large colonies, so it’s good for naturalizing. Small white flowers in May. Great fall color, purple to maroon. Showy red fruit forms in late summer and remains into winter or until birds pluck it all. A workhorse, adaptable to various soils and moisture conditions. Sun or half shade.

Koreanspice viburnum (Viburnum carlesii)

Rounded, dense shrub, 8 to 10 feet by 8 to 10 feet, unless you happen upon the half-size variety ‘Compacta.’ White flowers in showy round clusters in late April or early May fill a yard with outstanding spicy scent. Might develop shining red fruit if there are viburnums nearby that are closely related. Fall color sometimes a pleasing maroon.

Laceleaf red elder (Sambucus racemosa varieties)

Upright woodland native with white flowers in flat-topped clusters in early summer, followed by red berries. 10 feet tall. Look for the half-size dwarf and gold laceleaf forms.

Leatherleaf viburnum (Viburnum x rhytidophylloides)

Upright, 12 to 15 feet. Tree-like, especially in shade where foliage is most dense at the top of the plant. White lace-cap flowers in May, berries in June and July that age from red to black. Coarse foliage that’s dusky purple in fall. Fast to grow, very tolerant of shade and semi-evergreen to evergreen, so it’s very useful as a screen.

Panicle hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata)

Large white flowers in conical clusters in July or August age to pink and persist through winter. Many varieties. 8 to 10 feet tall and twice as wide, but about half that if cut back to the ground every year or two. Blooms on new wood so is reliably showy even where winters are harsh or it’s pruned hard. Sun to part shade. Very tolerant of shade but develops fewer blooms.

Onondaga viburnum (Viburnum sargentii ‘Onondaga’)

8-foot upright shrub, like a small tree. Foliage emerges maroon, changes to glossy green with a rose tinge for summer and glows red to purple in fall. Flowers in lacy, flat-topped clusters in May are deep pink in bud, white in full bloom, then salmon with age. Full sun to part shade.

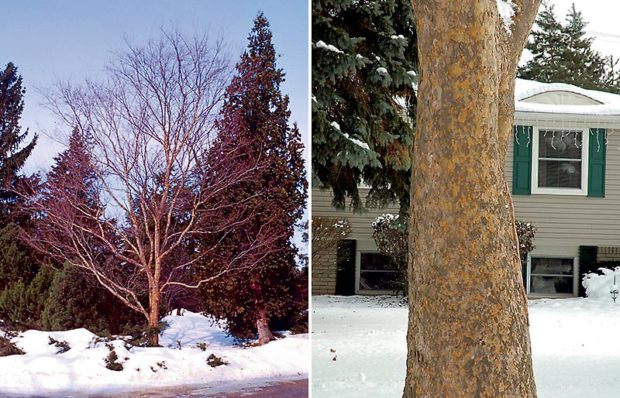

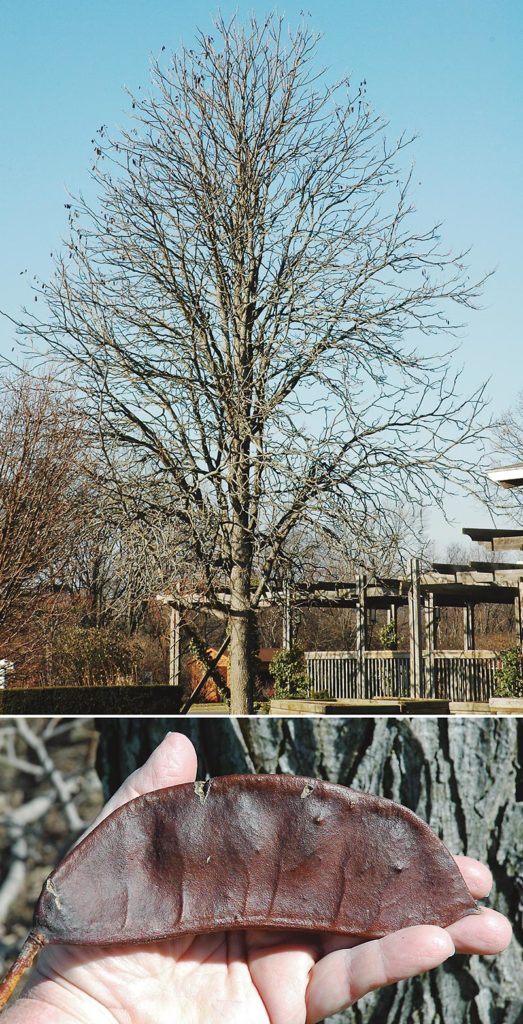

Seven-son flower (Heptacodium miconioides)

Upright shrub, tree-like, fast growing to 15 to 20 feet. Showy, extremely fragrant white flowers in September become attractive pink seed pods in October. Peeling bark is ivory, white, and parchment—very attractive in winter. Full sun to part shade.

Spring witch hazel (Hamamelis mollis and H. vernalis hybrids)

10 feet tall and wide, with dramatic horizontal branching and most foliage held high. Use it like a small, broad-topped tree in almost any light situation. Best in the half shade. In full sun the plant’s lines are less dramatic and foliage may scorch in summer. In the shade flowering will be less heavy. Yellow to orange or red, sweetly fragrant flowers in February and March. Butter yellow, apricot, or glowing orange fall color. Many good varieties. One special favorite is ‘Jelena,’ with red-orange flowers and orange fall color.

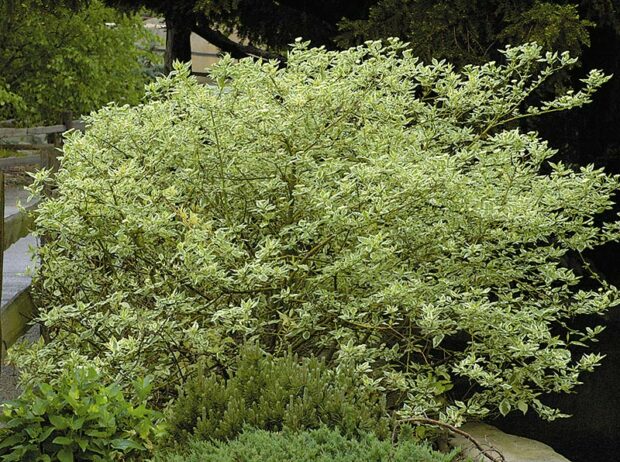

Variegated redtwig dogwood (Cornus alba ‘Elegantissima’)

White-edged leaves, red twigs in winter, 8 feet tall and 12 feet wide, but half that size if old wood is cut out each spring to stimulate more bright colored new wood, or the whole plant is cut to the ground every couple of years in spring. Flowers white on year-old and older wood, then bears blue berries in midsummer that are eaten by birds. I love this redtwig best but there are many other great varieties, some with gold-edged leaves or twigs more orange, scarlet, or maroon. Part shade. With plenty of moisture, it grows well in full sun.

Big, with one main show

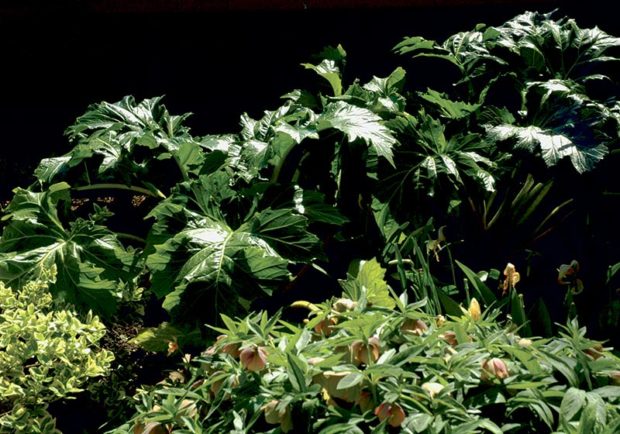

Bottlebrush buckeye (Aesculus parvifolia)

Big, bold foliage on a suckering shrub that holds up hundreds of ivory candles each June or early July. Fall color is yellow at best and in winter the shrub is nearly see-through. I love it because the hummingbirds love it—and for its fresh, showy bloom after all the spring shrubs have finished. I expect it to be 8 to 10 feet tall and wide (and accept that we’ll have to remove suckers beyond its allotted space) but know it can be twice that if it really likes the site. Sun or part shade.

Fragrant honeysuckle (Lonicera fragrantissima)

6 to 10 feet tall and round. A wallflower in terms of leaf and form—even a bit shabby in winter for its thin, arching, and somewhat disordered branches. Still, unmatched for very early spring fragrance. Give it a spot in the background or hedge. Full sun to part shade.

Quince (Chaenomeles speciosa)

Densely branched, glossy-leaf shrub makes an outstanding, unmatchable show of scarlet, rose, or salmon in May followed closely by red-purple of the emerging foliage. 8 by 8 feet, dense, deep green, suckering and thorny, it’s an impenetrable hedge or stand-alone thicket. I wish more properties had room and more gardeners the tolerance to grow it. Orioles and hummingbirds love its flowers and small birds its shelter. Full sun; don’t be taken in by the claim that it tolerates shade, which it does only at the cost of its primary asset: the bloom. Newer thornless varieties are available.

Snowmound spirea (Spiraea x vanhouttei)

White lacy flowers in dense clusters along the arching stems in May and June. A shrubby mound so densely twiggy it’s a screen even when leafless in winter. Blue-green foliage is sometimes a nice peach in fall. Larger but more graceful than Japanese snowmound. Birds love its shelter so much it never needs fertilization for all the droppings that fall there. Fast growing to 8 feet tall and wide. Full sun but very tolerant of shade.

Summersweet (Clethra alnifolia)

5 to 8 feet tall and not quite as wide. White or pink-tinged flowers on finger-length wands in July. Some varieties are shorter, later to bloom or have more pink in the flower bud. The best feature of the plant is the spicy sweet scent. Foliage is clean green in summer and sometimes copper in fall. Attractive to hummingbirds. I cut summersweet back to the ground every 2 or 3 years to keep it small; since it blooms on new wood that never stops the flower show.

Ural false spirea (Sorbaria sorbifolia)

Ferny-leafed shrub covered in feathery white plumes in July which repeat in August. Attractive to butterflies. 10 feet tall and as wide as you allow it to sucker. Blooms on new wood so can be cut to the ground each spring, in which case it is 5 to 6 feet tall. Variety ‘Sem’ is half size, even when left un-cut. Nice coppery color as the foliage emerges early in spring, and sometimes peachy in fall.

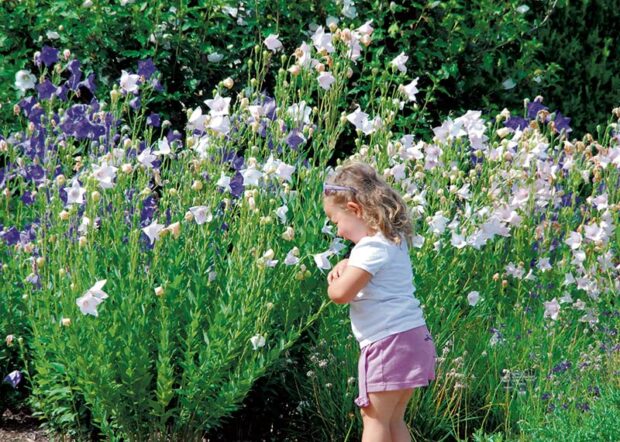

Satisfactorily small and multi-talented

Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

Dense, reliable shrub for full sun. Greatest return from varieties with red, gold, and variegated foliage. 6 feet tall and wide. Density and nasty thorns make it an excellent mounded, no-prune hedge. If you must have a rectangular hedge, plant an upright form such as ‘Sunjoy Gold Pillar’ and skip the pruning with its painful clean-up. Dwarf, mounded 18-inch by 36-inch forms are delightful (‘Gold Nugget,’ ‘Crimson Pygmy’). Insignificant flowers, may have red berries in winter.

Beautyberry (Callicarpa dichotoma)

A wide mound of nearly horizontal stems, 3 to 4 feet tall. Tiny flowers in July become clusters of purple fruit lining the branches. A showstopper in October when the leaves go golden and the fruit is the most purple. Full sun or part shade. Blooms on new wood and can be treated as a perennial, cut to the ground each year.

Blue mist spirea (Caryopteris x clandonensis)

5-foot round mound of gray stems with gray-green foliage and lacy blue flowers in August. All parts of the plant are sweetly fragrant. Blooms on new wood so can be cut to the ground each spring (and branches may die back in zone 5 anyway). Cutback and dieback shrubs usually reach only 3 to 4 feet. Gold-leaf variety ‘Worcester Gold’ and related C. divaricata ‘Snow Fairy’ with white-edged leaves show off their flowers to even greater advantage. Full sun. Don’t believe claims of shade tolerance—only in sun does it develop good bloom and scent.

Creeping cotoneaster (Cotoneaster adpressus)

12- to 18-inch horizontally branching shrub with pink or white flowers in June, then red berries that can be very showy in fall and persist into winter before being eaten by birds. Great for covering ground since it spreads by rooting where branches make good contact with soil. Full sun.

Dwarf spirea (Spiraea x bumalda)

2 to 3 feet tall and wide. Branches honey brown and so dense that the plant is a significant presence even when leafless in winter. Pink, rose, or white flowers in June and July will repeat in August if the shrub is sheared to deadhead it. Blooms on new wood and can be grown as a perennial, by cutting it to the ground each spring (the first bloom will be delayed into July). Some varieties have colorful foliage in summer (‘Gold Mound,’ ‘Lime Mound,’ etc.) and some have seasonally changing color (‘Gold Flame’ begins orange in spring, is gold in summer and orange once again in fall). Best in full sun but tolerant of part shade.

Kalm’s St. John’s wort (Hypericum kalmianum)

2- to 3-foot round, dense, with blue-green leaves. Makes a good foil for spring-blooming perennials and then picks up the garden with bright yellow, furry-centered flowers over many weeks beginning in July. Full sun.

Slender deutzia (Deutzia gracilis)

Dense, twiggy plant that manages to bloom almost as well in shade as sun. 4 to 6 feet tall and almost as wide, dwarf ‘Nikko’ is half that height and broader than tall. Gray twigs can be a pretty structure in winter in combination with evergreen perennials. White dangling flowers all along the branches in May.

Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica)

Arching stems, 4 to 5 feet tall (half height in dwarf forms such as ‘Little Henry’). Part sun. Native along moist streambanks in sun and shade where it suckers to form groundcovering colonies. Blooms white in June but grow it where you will see its most valuable asset: the very late, glowing red-purple fall color.

Evergreens

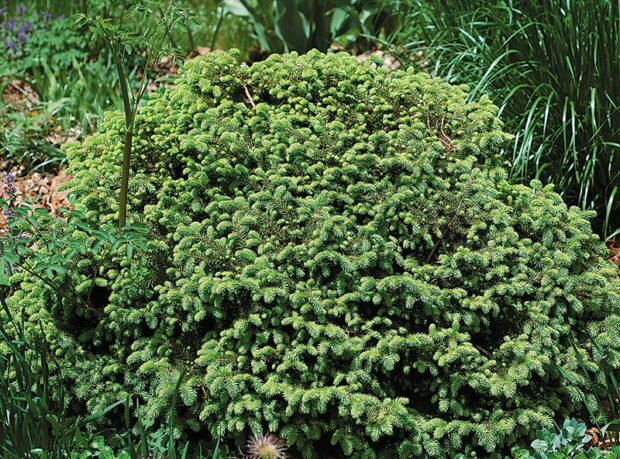

Bird’s nest spruce (Picea abies ‘Nidiformis’)

Irregularly mounded, dense, and eventually 4 feet tall and twice as wide. It may develop a depression in top center. If it must be kept smaller than its potential, prune every year or two beginning as soon as it reaches maximum allowable size. Full sun to part shade.

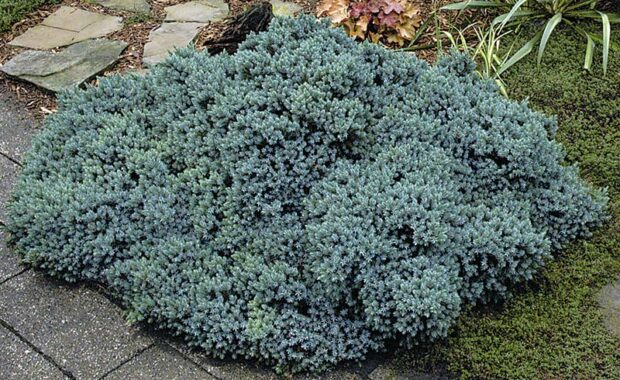

Blue star juniper (Juniperus squamata ‘Blue Star’)

Its blue foliage is bright in summer, steely in winter. Slow to grow and compact, might eventually be 2 feet tall and half again as wide. Has rather brittle branches so don’t plant it where feet may stray or snow might be stacked in winter. Full sun.

Dwarf white pine (Pinus strobus ‘Nana’)

Mounded or wide, irregularly spreading, light green plant with long, soft needles. Luminous in winter. May reach 6 feet tall and 10 feet wide but can be kept smaller if pruned every year or two beginning as soon as it reaches the desired height and width. Full sun to part shade, and amazingly tolerant of shade although much more open and slow growing there.

Goldthread falsecypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Filifera Aurea’)

Mound of feathery, gold-tipped foliage forms a broad pyramid 10 to 15 feet tall. Dwarf varieties include ‘Golden Mop,’ ‘Vintage Gold,’ and ‘Lemon Thread.’

Hinoki falsecypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Nana’)

Very dense, slow-growing dwarf with irregular fans and ridges, very dark green foliage and brighter green new growth. It has the look of a dark green, coral outcrop. 2 feet tall and half again as wide. Full sun to part shade.

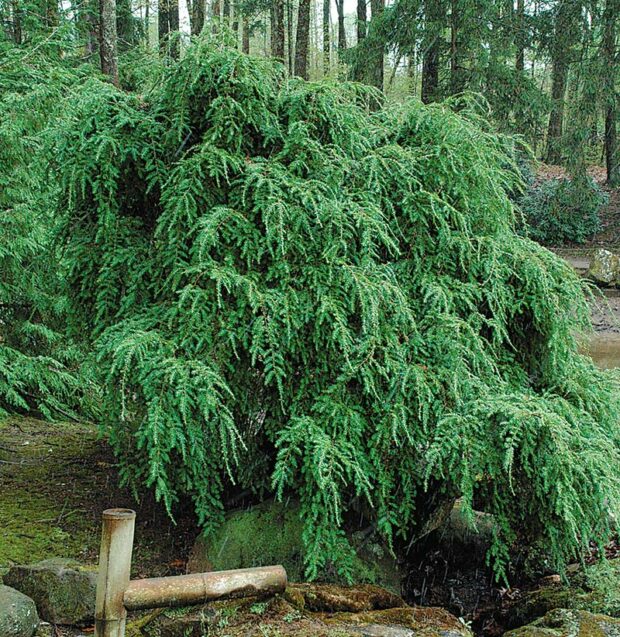

Sargent hemlock (Tsuga canadensis ‘Sargentii’)

The king of feathery evergreens, it makes a graceful mound 8 feet tall and 2 or 3 times as wide, or a small weeping tree. Part shade or sun.

Ward’s yew (Taxus x media ‘Wardii’)

Dark green, dense, wide-spreading beauty in sun or shade. Red “berries” in winter add interest. 4 to 8 feet tall and 10 feet wide or wider. Can be kept smaller, even sheared into geometric forms, but is best used if grown for or pruned for its graceful natural form with feathered edges. For hedges and sheared shapes, use the more regularly-shaped, upright ‘Hicks’ or rounded ‘Densiformis’ yews.

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.

RELATED: See “Website Extra: Janet’s Guide to Shrubs” for additional useful lists for shrubs in this article, such as:

- Shade

- April/May/early June bloom

- Bloom in late June or later

- Fragrance

- Fall color

- Birds and butterflies

- Winter interest

- Screen or hedge

- Colorful fruit

- Colorful foliage in summer

- Long lived without pruning

- Hardiest

ELSEWHERE: A homeowner’s guide to nutrition and fertilization of landscape trees and shrubs