By Janet Macunovich / photos by Steven Nikkila

As a garden grows, so grows the gardener.

I spent a summer in England, ostensibly as nanny to a four year old niece. There, the brothers Cameron changed my life. These men—I never knew their first names, addressing both as “Mr. Cameron”—were caretakers of a church in Shenley Church End, Buckinghamshire. A Cameron had been the church caretaker, lived in that home, and tended the walled cottage garden since the late 1600’s.

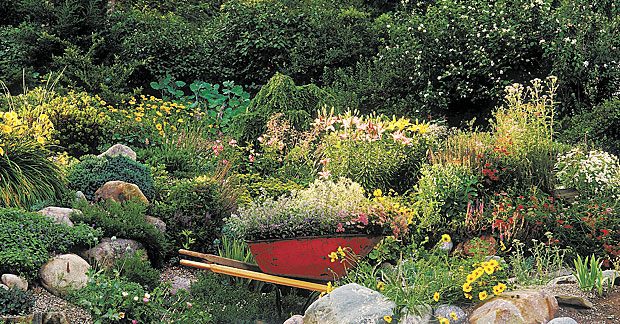

My first visit was in early June when the elder Cameron found me studying headstones in the church graveyard. He asked me into the garden for tea. I invited myself back to talk flowers, and returned throughout the summer to run wheelbarrow and dig for the two, then 70 and 80 years old.

Back home in Michigan that fall, I dug over the garden I’d left behind and planned to change it from rows of vegetables and annuals to perennials. It went fallow into the winter, insulated under a thick layer of leaves, ready for a grand metamorphosis. I spent that winter buried in catalogues, searching out the seeds of plants I’d coveted through the summer, unaware of how much I myself was changing.

Now, more than a quarter century has passed and with it the Camerons’ garden and even Shenley Church End—swallowed in a conglomerate community called Milton Keynes. The church is closed, lost in a hard-to-find siding off the new traffic flow. Looking into the walled yard attached to the deserted caretaker’s house, you see only the field grass and weeds that come to abandoned ground everywhere.

Yet the inspiration I took from that delightful garden still grows.

Initially, I mistook its nature.

I worked happily in my garden for years, thinking to reproduce the plants, the sitting areas, the gracefully trained vines of the Camerons’ retreat. I felt some regret as my palate expanded to include species that were probably never available to the Camerons—it seemed I would leave their garden behind. After several seasons more, I was surprised to see that the similarities between what had developed here in Waterford and what had been there in Buckinghamshire were still greater than the differences. I understood then that my real goal had been and still was to recreate the feeling of that English garden, not a replica of its beds.

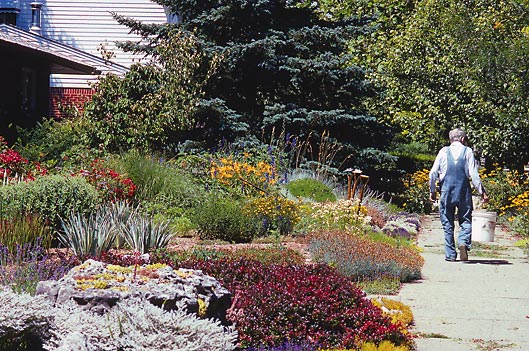

More recently, I doubted the value of pursuing that feeling. When I began gardening on others’ properties as much or more as I gardened on my own, the thrill of the new garden claimed me. Working in my own beds was not as much fun as creating a garden from non-garden. Stripping sod, outlining beds on a clean slate, watching a design move from paper to reality produced a creative high that was tough to find except in a new garden. To make anything truly new in an established garden, so much energy had to be expended in preparation, just to clear away existing plants and memories!

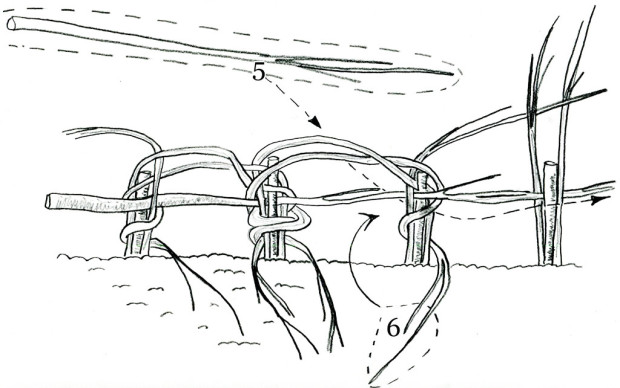

Established gardens began to seem more trouble than they were worth in other ways. Plants overgrew their bounds, sometimes in ugly or destructive ways only partially remedied with tedious pruning and awkward restraints. Weeds that sneaked in and became entrenched could sometimes be eradicated only through wholesale slaughter of, or painstaking lifting and cleaning of desirable plants. Pests sometimes claimed the upper hand, particularly as conditions changed around older plants. Looking at sections of garden left thin and raw for these and other reasons, I began to think it would be better to tear everything out and start new every five or six years, or move to a new gardening site entirely.

Today, I’m back on the Camerons’ track. I have identified the seed which germinated in me back then as love of Hortus venerablus—the old garden. Even with its limitations, its advantages are overwhelming. It’s now inextricably rooted in my heart.

To name just a few advantages, beyond the obvious ones of mature hedges and trees that cast shade…

In a garden tended over many years to discourage weeds, the seed bank in the soil shifts. Where it may once have had a high proportion of crabgrass seed—a species which can survive 20 years in the soil, waiting its chance to rise to the surface and sprout—it may eventually contain more daisy and coreopsis than dandelion, more globe thistle and coneflower than chickweed. Bare the soil in a new garden and stand ready to hoe lamb’s quarters, dock, pigweed and spurge. Pull the mulch back from a bit of old bed and prepare to thin volunteer candytuft, pimpernel, campion and cranesbill. Weeding the cracks between new paving stones is a chore. Weeding the same spaces in an older garden, the tedium is broken by discovery and decisions to leave that patch of sweet alyssum, step over that seedling sedum, and allow that pesky Perilla to stay and shade out any other comers.

Only over time do natural organisms of all sizes take hold and reach a balance with each other. Fungal and bacterial diseases seem to move in first, but if the gardener keeps a level head and avoids trying to make the environment antagonistic to all such, a far greater number of benign and helpful microorganisms soon take hold. Some of these decompose organic matter, replacing store-bought fertilizer. Others infect and kill pests. Some are known to muscle into spaces each spring before their disease-causing relatives can reach them, creating a no-room-in-the-inn squeeze play that suppresses the proliferation of the baddies.

Worms, insect-eating insects, amphibians, birds and small mammals move in as the organic matter and smaller organisms they feed on become plentiful enough to support families. No wonder my long-ago trial with a hummingbird feeder failed! We should try again, now that there is so much better habitat, more water, more insects, an absence of bad-tasting pesticides and a wealth of alternative food sources. But then, why bother? The hummingbirds are here!

A client, relatively new to gardening, once wanted me to transplant a particular plant from my garden to hers, and took offense when I declined the work. She didn’t understand my explanation that the plant’s above ground appearance was a direct reflection of an extensive, old root system and an equally extensive network of life in the soil. Simple refusal would have been my best route because the to-your-bones understanding of that situation usually comes only with experience and years. She would have to learn for herself that no amount of skill with a spade can succeed in a lasting transfer of the essence of old.

A client, relatively new to gardening, once wanted me to transplant a particular plant from my garden to hers, and took offense when I declined the work. She didn’t understand my explanation that the plant’s above ground appearance was a direct reflection of an extensive, old root system and an equally extensive network of life in the soil. Simple refusal would have been my best route because the to-your-bones understanding of that situation usually comes only with experience and years. She would have to learn for herself that no amount of skill with a spade can succeed in a lasting transfer of the essence of old.

The thrill of the new still exhilarates me—I count myself fortunate to be able to feel it in large doses in clients’ and friends’ yards. Yet as an admirer of age, I’m also happier in my older beds, as delighted watching things grow as I am at their maturity. The “routines” of maintenance are more enjoyable and the unrealistic expectation that things will ever be and stay “done” crops up less. I may even be learning to coach others in cultivating an appreciation of both aspects of gardening.

Oh, to sip tea with the Camerons today, and talk to them of these things. How we might laugh over what I said and did then as I plotted to transplant Hortus venerablus!

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of the books “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet on her website www.gardenatoz.com.