Our gardens are reflections of who we are as people

by Janet Macunovich /

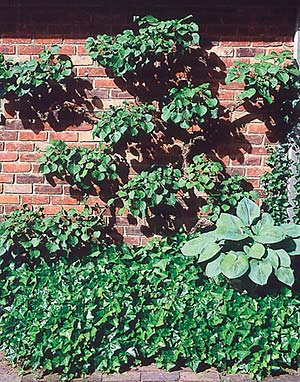

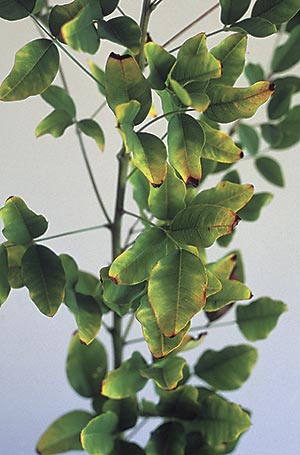

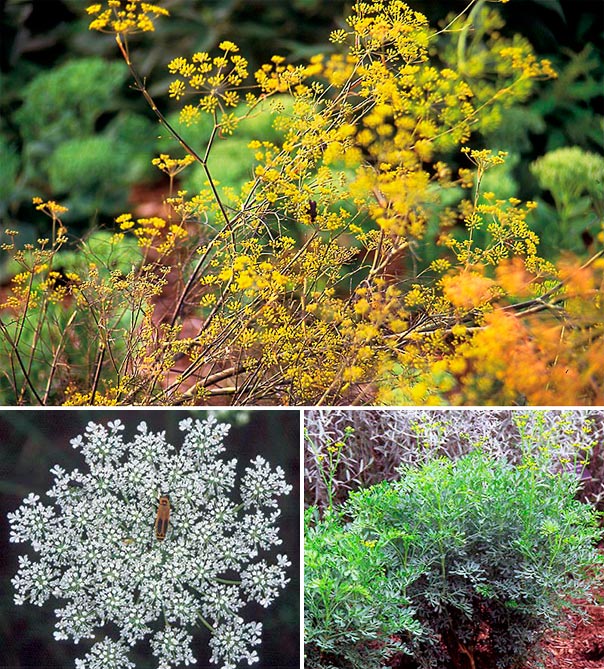

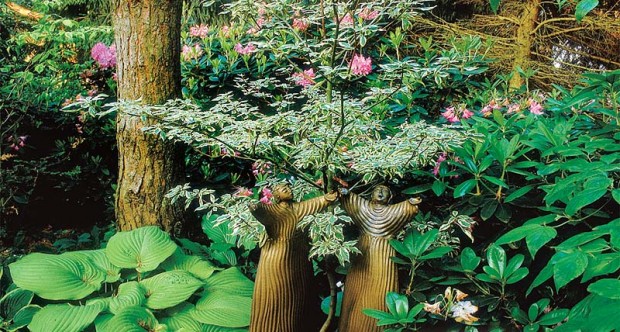

Photos by Steven Nikkila

First, we talk to the plants. Then, they begin to talk to us. Simply at first—“I need water!”—but eventually they speak with more eloquence—“I would appreciate some micronutrients in my water, darling. And could you see to my friend here? He is making me itchy with his spider mite condition and I’d be greatly relieved if you’d rinse him thoroughly!”

Why was I surprised then, to find that the whole garden begins to tell tales on its gardener? Once I tuned in to the language, I found it was fascinating, a whole new dimension to enjoy.

General-garden and whole-landscape messages follow the same progression from simple to complex that individual plants use as they teach us their language. In the beginning, we may understand only the most obvious statements, such as “This is the door my gardener would prefer you use.” Given time and gardening experience, though, more subtle signs become clear and can apply to almost any issue. These higher-order statements may point us to the best seat in the yard or clue us in to how the gardener in residence really feels about guests—whether he or she truly wants visitors or would prefer they simply stand and look, then go away.

The language is most coherent in the true gardener’s garden. As a baby might delight us with playful use of a few sounds, so does a novice planter convey very basic messages of joy or frustration when they work with a flat or two of annuals. Advanced gardeners speak with a much greater vocabulary. Some people wear their hearts on their sleeves. Gardeners grow to display theirs in the landscape.

Gardenspeak is not alphabet-based, but more like hieroglyphic or Chinese writing. Since its individual characters are so complex, a good reader can form an overall impression of the message’s tone just from the quality of the writing—whether the glyphs are rendered crudely, with competence, or are works of art. Because the characters themselves are more fluid than letters in an alphabet, it’s possible for a master, using only tiny strokes, to change any ideogram into something quite different in meaning. When we garden we write in just such a complex, liquid code made up of our choice and placement of plants, the composition and condition of our paths, the siting and comfort level of seating, and much more.

In this code our gardens make it quite clear where we spend our time—not just what our favorite spots are in a garden, but where we most often are in the building the garden surrounds. They also describe what seasons of the year are important to us. In the landscape and garden are written a person’s life history—what environment they knew as a child, the schooling they had, what attachments they have to other people, whether they own pets, even what the person’s profession is or might be one day. With practice and a gardener’s eye we can decipher another gardener’s hopes and dreams, personal philosophy, and demeanor.

Before this season ends, while there is time to plan changes for next year, look at what your garden is saying about you!

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.