For years, our holly bushes have been lush with fall holly berries, but not last fall. I think they got their fair share of water during the summer heat wave. Any thoughts?

Think back to April 2012 and what happened with the late frost and freezing temperatures at the end of the month. Many of our beloved spring-flowering trees were heavily damaged at a critical time in fruit formation. The holly bushes were no exception. Even though the buds form in the fall of the previous year, April would have been the time these tiny flowers in the leaf base on male plants would have been opening. Many flowering shrubs and trees suffered great damage last spring due to the sudden cold temperatures. Michigan’s cherry and apple industries were significantly impacted by the cold snap.

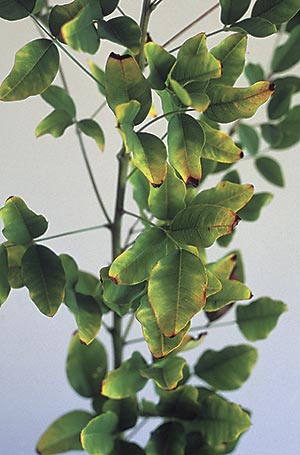

Although the holly plant is basically a male plant, their flowers and subsequent pollen are necessary for the fertilization of the flowers on the female berry-producing plants. If they aren’t there, the female flowers are not pollinated and there is no berry. Maintaining a consistent watering routine early in the summer as well as during drought periods will also prevent premature berry drop. Covering plants when a freeze is posssible can substantially decrease the loss of flowers and future berry production.

Related: What are some suggestions for deer-resistant plants?

Elsewhere: Winterberry: Michigan’s native holly