by Bev Moss

We are fighting an ongoing battle with nasty stinging nettle weeds. I pulled them a couple times last year, but they kept coming back. How do we prevent them from returning? K.L., Farmington Hills

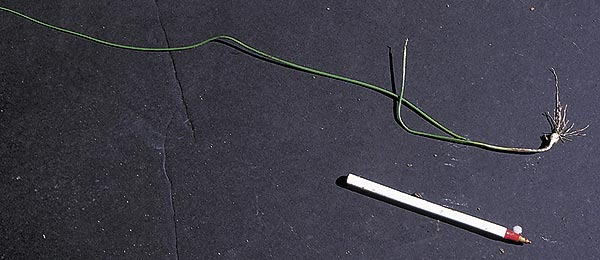

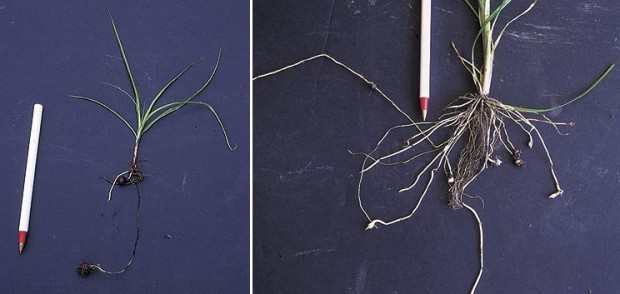

Stinging nettles (Urtica dioica) get their nasty rap from the sharp hairs on their leaves. These hairs inject irritants into the skin which then cause swelling and itching. You can neutralize the effects by applying soap, milk, or a diluted solution of baking soda on the affected area.

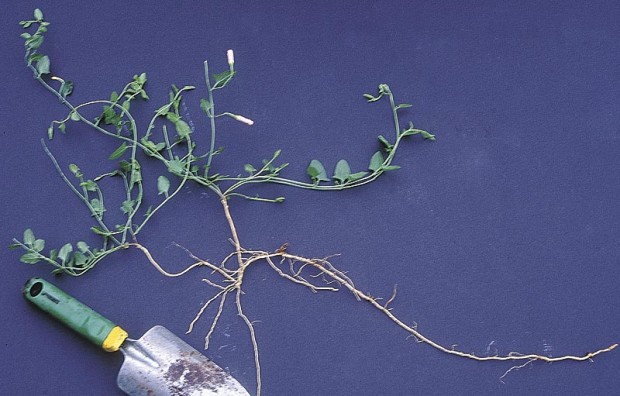

Looking similar to a stinging nettle, “white dead-nettle” is a hairy perennial with heart-shaped, deeply toothed leaves. Dense whorls of white, hooded flowers appear up the stem, among the leaves. So check www.canr.msu.edu/resources/stinging-nettle-urtica-dioica to make sure you have the right plant.

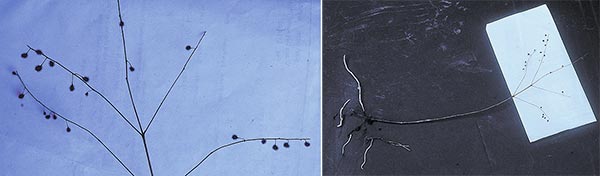

Pulling nettles only causes root growth as they form a rhizomatic network underground. Your best attack is to cut them off low to the ground before they flower and hand spray a solution of two percent glyphosate to the raw cut. This takes the herbicide to that plant root and prevents regrowth. You may have to do this several times over the course of a season to thoroughly stunt their repeat performance. Any seedlings that pop up can be dug out immediately before they create a mature root system and plant stems.

Check the border areas of your property to insure you do not have a hidden breeding crop. Seeds are plentiful from just one plant and can easily be moved by animal traffic.

Beverly Moss is the owner of Garden Rhythms.

Related: Dangerous Plants – A Healthy Respect Will Keep You Healthy