by Bev Moss

Are there any deer-resistant plants that will grow under large pine trees? Four feet of the bottom limbs have been trimmed off. There is a little bit of light, but the upper limbs block most of the rain. I tried hostas, but the deer ate them. G.R., Clinton Twp

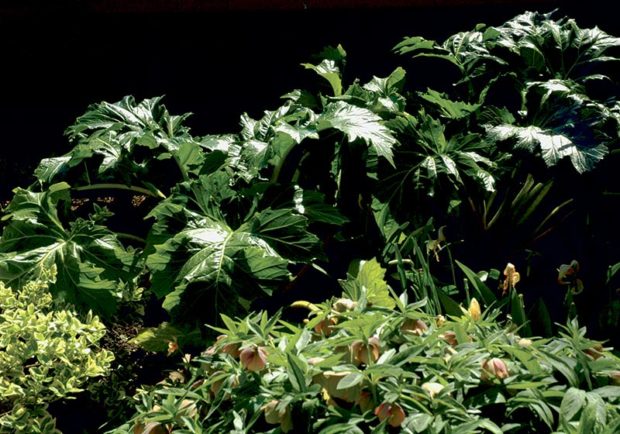

Dry shade and deer resistant are two of the most common requests in planting under trees. Forget the hosta buffet and look to early-flowering hellebores and the many varieties of epimediums. Even the exotic-looking hardy cyclamen likes dry shade. All are ignored by deer and have a nice range of flower color for spring into early summer and excellent leaf texture into the season. Look at the shorter varieties of astilbe as well as brunnera and lungwort, which have great mid-spring flowers and colorful leaves all season. Leaf texture and variegation take the place of flowers when blooming is done. There are a few ferns that will survive in dry shade. Christmas fern, maidenhair fern, and marginal wood fern will establish in those conditions and be disinteresting to deer.

Note well: to get established, all of these plants need regular watering in the first year. Create a 2- to 2-1/2-foot planting area around the dripline of the tree so they can benefit from rainfall and auxiliary watering. Consider a soaker hose woven through the plantings that you can hook up regularly to facilitate watering. Do not expect a plant to thrive up against the trunk of the tree where the canopy is darkest and water is negligible.

Beverly Moss is the owner of Garden Rhythms.

Related: What are some suggestions for deer-resistant plants?

Elsewhere: Smart gardening with deer: Deer-resistant bulbs to plant in fall