by Nancy Lindley

I can fondly recall the year my mother ordered one of every climbing rose variety from her Jackson & Perkins catalog. Her goal: create a continuous color mass on a new split-rail fence. Her excitement: high. Her desire: strong. Her results: blah.

I was probably about ten years old that year, and vividly remember helping plant all those dead-looking, bare-root rose bushes with peculiar names like ‘Zephirine Drouhin,’ ‘Don Juan,’ and ‘Golden Showers.’ But to my utter surprise and disbelief, they quickly grew long canes that ultimately sported a brilliant bouquet of colorful flowers that summer. Hooray for Mom! Our favorite was the newly introduced ‘Joseph’s Coat’ with its masses of bright yellow and red blooms.

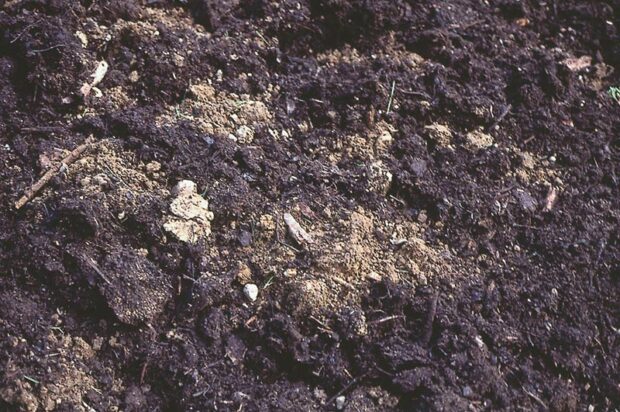

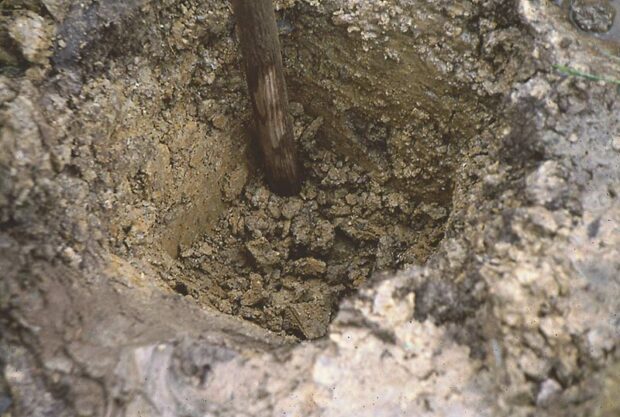

That fall, my mother tenderly hilled soil over the base of her darling climbers and securely tied them to the fence in preparation for winter. The following spring, all were dead.

Not one to readily admit defeat, my mother retreated to the rose book section of the local library and emerged with renewed vigor and determination. That summer, she replaced every bush with new climbers. Come fall, she put to practice her newly acquired knowledge: untie and bury the long canes in the ground.

The following spring, the results were remarkably similar to those of the first year. Thus ended my mother’s attempts to grow climbing roses.

What she didn’t know then, but we know now, is that many roses sold in this country aren’t hardy enough to handle Michigan’s climate. Yes, you can winter-protect tender hybrid tea roses by hilling them under mounds of soil. However, it’s almost impossible to protect the long canes of tender climbers. To succeed, you need to grow “cane-hardy” roses. Those my mother tried to grow die back too much each year to succeed as climbers here.

There are several types of roses that can be used as climbers. Some thrive in Michigan, others do not. I’ll describe the general categories of roses that are available, then discuss which are suitable for Michigan, and which are not.

Large-flowered climbers

These are what my mother tried to grow. They produce large, colorful, fragrant blooms in several waves throughout the growing season. The showiest display occurs in June. Their winter hardiness is highly variable. While my mom didn’t grow them, the climbers developed by the Kordes family of Germany are well-suited for our climate. One example is their red ‘Dortmund,’ which produces masses of large, five-petaled blooms. Another is the bright yellow ‘Goldstern,’ which is surprising in light of the fact that yellow roses usually aren’t winter hardy.

Climbing sports

Roses of this type that my mother tried to grow include ‘Climbing Peace,’ ‘Climbing Queen Elizabeth’ and ‘Climbing Iceberg.’ These are just lanky mutations of well-known garden roses. They’re stingy bloomers, very tender, and are just not well-suited for Michigan.

Shrubs trained as climbers

New types of these roses not only survive in Michigan, they thrive. This includes the rugged Canadian Explorer shrub roses, many of which can be trained as ironclad climbers. One variety of Canadian Explorer is the strawberry-pink ‘William Baffin.’ It’s so winter-hardy, it can be left on the arbor all winter, without special protection, even if you lived north of the Arctic Circle. Another is deep pink ‘John Cabot.’ It’s attractive when spread along a wall or fence. Medium pink ‘John Davis’ creates eye-catching vertical interest when trained up a pillar.

Ramblers

Don’t overlook this group of easy-care climbing roses. They’ve graced Michigan gardens for generations with their long, supple canes that respond well to training. Their bloom is fragrant, copious (typically covering the entire plant), and long (often stretching for 5 or 6 weeks). When not in bloom, ramblers often cover an entire fence with attractive green foliage. For your garden, consider the classic pink rambler ‘Seven Sisters.’ It’s beautiful, fragrant and requires minimal care.

Climbing miniature roses

These are an excellent choice for Michigan gardens, especially if you want “constant color.” One in particular, ‘Jeanne Lajoie,’ is a wondrous climbing miniature. Unlike most climbing minis, such as cherry red ‘Sequoia Ruby’ or peachy orange ‘Work of Art,’ ‘Jeanne Lajoie’ grows 8 to 10 feet instead of 6 to 7 feet tall. It produces masses of small, full, pink blooms throughout the summer and is well-suited for training up a pillar or obelisk.

How to grow climbing roses

Climbing roses have the same cultivation requirements as other roses:

- They need lots of sun. More sun means more bloom. Yes, some climbers will tolerate less-than-full sun, but they won’t be prolific bloomers.

- They need lots of water. Typically, more than what nature provides, especially during their first year.

- They are heavy feeders and should be fertilized several times a year.

- They require good air circulation for good health. Roses planted in areas where air circulation is poor and leaves don’t dry quickly are prone to fungal diseases like blackspot. Consider putting up a chain-link fence. While some view these as an eyesore, they’re actually better for climbing roses than solid fences or walls because they promote good air circulation.

When tying long, flexible canes of climbers to upright supports, use a soft material such as yarn or hosiery. Also, tie them loosely to prevent the canes from rubbing against the support on windy days. You’ll want to remove and reposition canes several times during the growing season, especially when the rose is young and growing quickly.

Pruning

Prune climbers in late April, just as the leaves are budding. If you want to prune out old, well-established canes, do so in late June after the first big floral display, not in late April. Otherwise, you’ll reduce the glory of the first bloom cycle. Do not prune climbers past mid-August.

During the first year, you should only need to prune dead wood or canes that cannot be directed toward a desirable location. In spring of the second year, prune all canes except for those that will be trained as main canes. Because the blooms appear mostly on the lateral side shoots, it’s important to prune these shoots by at least half during your early spring pruning. You’ll also want to remove spent blooms from lateral shoots throughout the growing season. In the third and subsequent springs, remove about 1/4 to 1/3 of the main shoots and train new shoots as replacements. This rejuvenates the bush and keeps it productive.

Climbing roses create a dramatic focal point on obelisks or pillars. On trellised walls, they provide privacy and reduce sun glare. On chain-link fences, they provide a softer, more welcome look. Of course, no matter where they are, they provide sweet, fragrant breezes.

Remember the two main keys to success with climbers: 1) select varieties that are cane-hardy to your climate zone, and 2) spend a little time training them. Do this, and you will be well rewarded for your efforts.

Nancy Lindley was the co-owner of Great Lakes Roses in Belleville, MI.

Related: Follow these five steps to grow fabulous roses

Elsewhere: Why are my roses changing color?