Plants that armor themselves against future droughts

After one of the hottest, driest summers in recent memory, we realized that quite a few species were not crispy critters, but actually seemed to be reveling in the heat and drought.

So I began noting plants in my own garden and others that rely almost entirely on rain, and made the following list. It’s hardly exhaustive—it’s heavy on perennials since that’s my gardening specialty, but even that list could be longer—but it’ll be useful for designing dry, gravelly beds or hot places where the hose won’t reach.

Don’t call it a list of drought-tolerant plants. Tolerance isn’t what you should settle for, because it’s not always pretty.

Joe Pye weed is a good example. They showed me their burned-back foliage, their drought defense mechanism. They simply hang on until late June, ugly though they may be with leaves so wilted you can pass your arm between stems without touching foliage, because then they can set buds for next spring. Even if they die back without flowering, those buds survive, insulated below the soil. It’s an effective survival technique, but hardly handsome.

So, some plants perfectly capable of outlasting a drought aren’t listed here. I sought and found plants that fare well in a drought and remain attractive too.

What makes these winners, when other plants shrivel or duck out in a hot, dry season? I’ve noticed a number of common characteristics that probably helped them survive. I’ll describe them so you can be on the lookout for other plants like them. Even without witnessing a plant’s performance under fire, you can probably bet on it if it has one or more of these attributes.

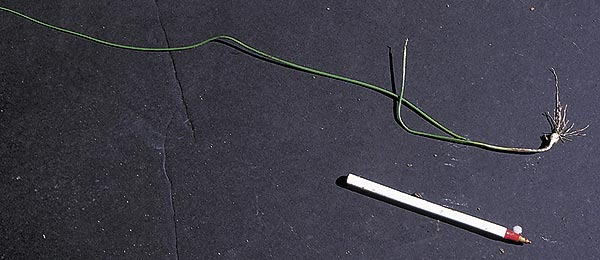

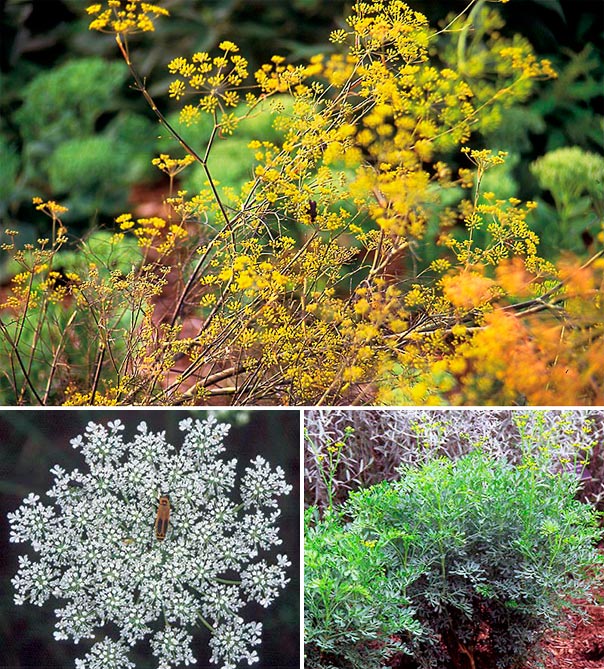

Plants with skinny foliage

The fewer and smaller its leaves, the less water a plant loses through transpiration on hot days. This was important this year, since some plants that might have weathered simple drought couldn’t handle the heat—they couldn’t take up water fast enough on the hottest days to replace what the leaves transpired.

Missing from the list are some plants with tiny leaves but a preference for dry air. Cosmos and annual bachelor button, for instance, are drought tolerant. Both are also susceptible to mildew when they’re under stress, as in a drought. Our high relative humidity insures that spores and chances of infection abound, so we see their lower leaves begin to brown and curl, victims of mildew.

Leaves held vertically

A leaf that stands upright escapes the full impact of midday sun. Bearded iris is a perfect example. It’s a plant that may never be as happy as when it’s planted in that hot, dry strip between driveway or sidewalk and brick house foundation. Yuccas and many ornamental grasses employ the same tactic.

Even large leaves can get by in a drought if vertically arranged. Prairie dock and its relative, compass plant, have huge leaves that stand straight up like canoe paddles stuck butt first into a sandy beach. Both plants impress me most in dry years, standing taller and producing sturdier flowering stems in a dry summer than wet (although prairie dock, a native of seasonally wet meadows, loves being wet at least through spring).

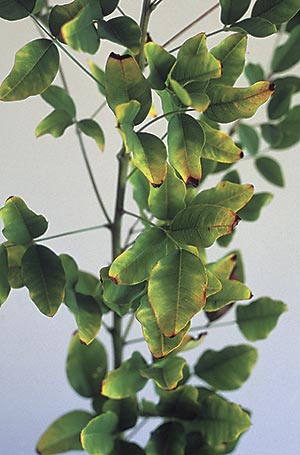

By comparison, and in explanation of some sad losses this year, pity the poor understory species often planted in the sun—flowering dogwoods, Japanese maples, redbuds, hydrangeas, etc. These plants’ leaves are held parallel to the ground, better to catch every photon of light that filters through the forest canopy. The only way for those leaves to protect themselves from full sun is to hang down—to wilt. In a wilted state they can’t photosynthesize, so the plant can starve in the process.

Leaves with a furry coat

The hair that makes a leaf look gray or silver also acts as insulation. Water released from “breathing holes”—the stomata—isn’t whisked away directly by the wind but remains trapped in the hairs as a high-humidity buffer zone.

Even a little bit of hair makes a difference—the downy foliage of a Tellima or the bristles on prairie dock and annual sunflower are examples. Excessive hair doesn’t seem to be the problem for plants that overdressing can be to people, however. Blue mist spirea and Russian sage, two of the best species for hot dry beds, have a coating not only on their leaves but the twigs too.

Leaves can fail to develop their rightful downiness if grown in cool, moist shade. Blue globe thistle and dusty miller are cases in point. They become almost green in the shade and apt to sag at the first taste of drought.

Waxy coatings on leaves

Here’s another means to slow water loss. Myrtle euphorbia’s (Euphorbia myrsinites) wax coating protects it even through winter’s freeze-drying, so I’m not surprised this plant looked blue, cool and comfortable all summer. And although giant crambes burned or were set back, their waxy blue cousin, sea crambe, never looked better than it did in this drought.

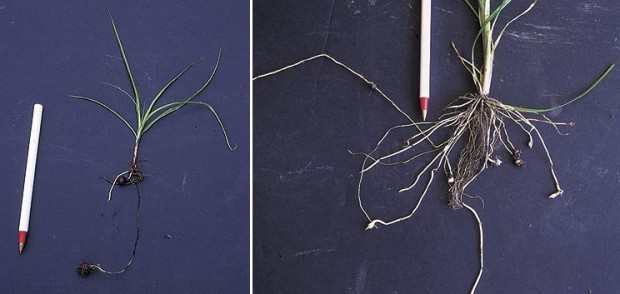

Tap roots

Plants that pull water from deep down can grow for weeks and even months after other plants have curled up and blown away. Tap roots are probes that can extend many feet into the subsoil.

Many plants have more than one defense mechanism. Waxy myrtle euphorbia has a tap root. Yucca and yucca-leaf sea holly (Eryngium yuccifolium) have vertically-arranged leaves as well as tap roots.

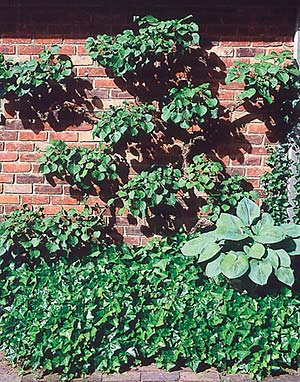

Wide-reaching roots

Far-flung, stringy roots carry junipers, butterfly bushes and hawthorns through a drought. These plants aren’t limited to drawing water from only that relatively small area right outside their own driplines.

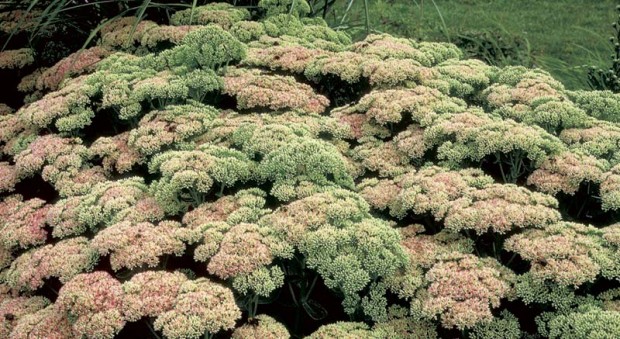

Succulent foliage

You probably know that cacti take up water during the brief desert rainy season and can retain and use it slowly, even over years. Michigan native prickly pear cactus and many sedums can also make use of water that was imbibed weeks before.

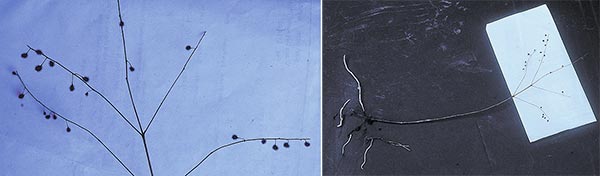

Bulbous plants and others with avoidance syndrome

Listen hard, and you can probably hear tulips, daffodils and foxtail lilies humming with delight right about now. These plants developed “grow fast, then hide” traits to deal with bone-dry summers. In fact, Michigan’s normally-moist summers may account for problems we have with these plants as perennials—namely, that they won’t come back. If the bulbs (tulip and daffodil) or roots (foxtail lily) remain cool and moist all summer, they don’t ripen. As a result, they may not set flowers or might not develop a proper protective tunic, which may mean they’ll rot during winter.

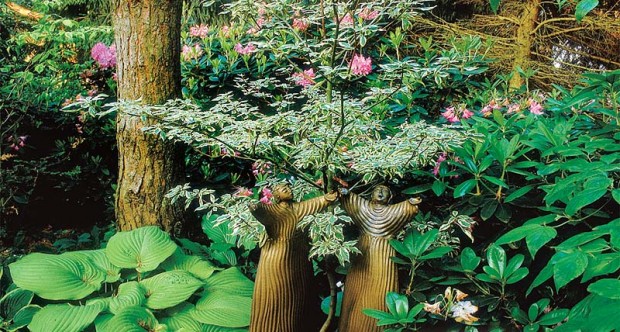

Beats me what gives them an edge

Then there are the plants who survive by some facility I can’t figure. Yet even though I can’t guess why ‘Gold Standard’ and ‘Sugar and Cream’ hostas keep going when other hostas are toasted or prostrated by the heat, I can’t deny my notes—they did stand tall. Tovara, Solomon’s seal and goatsbeard stump me as well, as does siebold viburnum—this last has hairy leaves and twigs, but so do other viburnums that scorched and drooped this summer!

Most of these enigmas are shade-loving plants, and as such are not likely to withstand drought and heat if moved out of their element. However, I’m convinced that shade alone did not save them. Many were survivors in shade gardens among dozens of other shade-loving species that wimped out.

One last thing. If you choose to grow a perennial or hardy woody plant from this list, don’t simply set it out in a dry bed and expect it to thrive. If it was produced in a nursery or an irrigated bed, even if it belongs to the most drought-tolerant species in the world, it will need time to reconfigure its root system from a dense, watered-every-day ball to something wide, deep or both. If it’s a species shielded by furry foliage or a thick, waxy coating, it may come to you less hairy or thinner-skinned than it should be. Once established, things are different, since the plant’s leaves will form in hotter, drier conditions. So provide water during dry spells for at least the first year if you want to see your drought-tolerant plants shine the next time rains fail.

Drought-thriving plants

Annuals

- Dusty miller (Senecio cineraria)

- Gazania

- Licorice plant (Helichrysum species

and varieties) - Red fountain grass (Pennisetum setaceum ‘Rubrum’)

- Sunflowers (Helianthus varieties)

- Verbena bonariensis

Perennials

- Allium (Allium species)

- Amsonia (Amsonia tabernaemontana and A. hubrichtii)*

- Baby’s breath (Gypsophila paniculata)

- Barrenwort (Epimedium species)*

- Bearded iris (Iris germanica hybrids)

- Blue globe thistle (Echinops ritro)

- Blue lyme grass (Elymus arenarius, Lymus arenarius). Beware: it’s not a clump-former but a runner extraordinaire.

- Butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii and its hybrids)

- Catmint (Nepeta mussinii and hybrids)

- Compass plant (Silphium laciniatum)

- Daffodil (Narcissus species and hybrids)

- Dianthus ‘Bath’s Pink’ and other perennial carnations having D. gratianopolitanus in their genes.

- Fountain grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides)

- Foxtail lily (Eremurus himalaicus)

- Goatsbeard (Aruncus dioicus)*

- Goldenrod (Solidago species and hybrids). Note: it’s not an allergen and there are excellent clump-forming hybrids such as ‘Goldenmosa’ available.

- Hosta ‘Gold Standard’*

- Hosta ‘Sugar and Cream’*

- Lavender mist meadow rue (Thalictrum rochebruneanum)*

- Leatherwood fern (Dryopteris marginalis)*

- Michigan lily (Lilium michiganense)*

- Myrtle euphorbia (Euphorbia myrsinites)

- Perennial ageratum (Eupatorium coelestinum)*

- Prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum)

- Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa)

- Rose mallow (Lavatera cachemiriana and Malva alcea)

- Sea crambe, sea kale (Crambe maritima)

- Showy stonecrop (Sedum spectabile and hybrids such as ‘Autumn Joy’)

- Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum species)*

- Starry false Solomon’s seal (Smilacina stellata)*

- Tellima (Tellima grandiflora)*

- Tovara (Tovara virginiana, Persicaria virginiana)*

- Tulip (Tulipa species and hybrids)

- Yucca (Yucca filamentosa)

- Yucca-leaf sea holly (Eryngium yuccifolium)

Shrubs

- Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

- Blue mist spirea (Caryopteris x clandonensis, gray-leaf forms)

- Juniper (Juniperus species)

- Siebold viburnum (V. sieboldii). Caution: fragrant in bloom, but not in a nice way.*

Trees

- Hawthorn (Crataegus species)

- Honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

* Should be grown in shade or half shade.

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.