Gardening has never been easier. Power equipment, ergonomically efficient hand tools, landscapes featuring groundcovers and mulch rather than labor-intensive hoed flower beds, inexpensive materials for no-bend raised beds, and lightweight prepackaged potting mixes all ease the strain of the garden season on muscles, bone, timetable and checkbook. It’s great.

But there is a consequence of all this efficiency and mechanization that causes me concern. Those long-reach tools, no-fuss plantings and time-saving schemes put distance and time between the gardener and his garden. Yet spring is a time to embrace the garden!

Don’t we get enough separation from our gardens from November to April? Shouldn’t we be kissing the ground, hugging our shrubs and stroking the silky new bulb foliage once the snow melts? That’s what I do.

Not only does it make me feel better to reconnect, but it keeps me ahead of trouble and on the easy side of the street for the whole year.

Here’s my spring start-up routine.

When the bulb foliage is up several inches and perennials’ basal rosettes have begun to show new green, I know the soil in that area has drained and warmed enough to accept my ministrations. In my own beds and most others I’m involved with, I expect to be out there on April 1, although I do work in a few beds that are too low, poorly drained or so shaded and sloped away from the sun that plant growth is retarded and I wait until later in April.

It helps at this time of year to summon one of my alter egos to coax, prod, push or fire me up and send me out the door, because an April morning can seem cold and unappealing. Even though I’ve learned that every hour I spend in early April saves me triple time later in the year, and I know that it will be less than an hour before I’ve warmed up enough to peel off my first layer of insulation, the first step out of the house can take work.

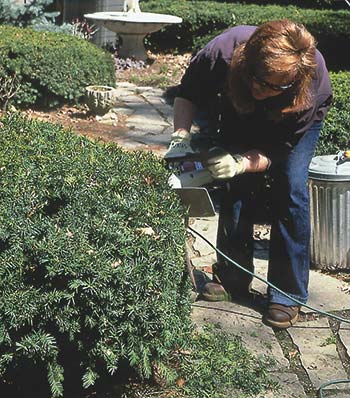

My first and most important job is to visit the plants and see how they’re doing. So I crouch, pruners in hand to clip away last year’s stems from perennials and damaged bits from shrubs, and give each member of my garden the once-over.

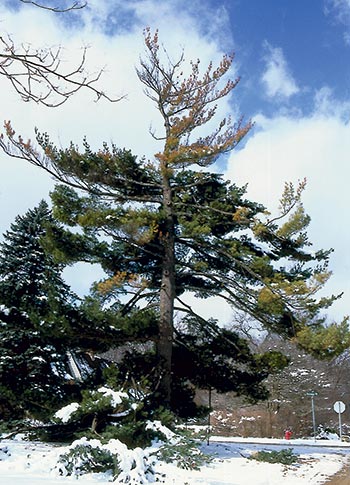

I’m not doing anything other than clipping yet, but I’m noting things like the presence of weeds in or near the crown, animal damage, weak or rotted portions, overcrowded clumps or over-eager colonies, and puzzling unknowns. After 30-some years watching my plants wake up, I pretty much know my team. Each species has its own character and unique weaknesses. Some always jump up ready to rock, some winter restlessly and need untangling from the sheets, and a few need to be hustled quickly to the vanity for a makeover before polite company arrives. Occasionally one needs doctoring or inoculation because I see early signs of that plant’s unique recurring problems.

There are always a few new guys every year who give me pause. Getting to know each one is like learning the ways of a new friend, one day and one encounter at a time. In spring, I scribble my observations on a mental clipboard.

As I cut, I toss plant debris over my shoulder onto the lawn or a tarp. Every 10 or 15 minutes I stand up, pocket the pruners and stretch out with a rake to clean up my clippings. It’s unwise in early spring to spend too long in any one position or motion.

If the bed needs fertilizer, I broadcast a slow-release, organic product. I do this now so that the granules of fertilizer will be mixed into the top few inches of soil as I do my next steps—weeding and dividing.

I weed the bed beginning where most weeds begin—on the edge. Most of the plants we call weeds get into a bed as creeping roots or from seed dropped from the plants just outside. If I keep the edge free of weeds, the middle of the bed can almost fend for itself. After one good weeding in April I generally have very little weeding to do in May and often none in June, July and August.

I cut along the edge with a spade, separating runners from their source and loosening the soil. Then I lift out seedlings and creeping infiltrators, chasing every bit of running root. If there is a root barrier such as edging surrounding the bed, I loosen and lift seedling weeds all along the perimeter and check to be sure that defensive barrier is working. Sometimes I find that running root plants are coming in over the top of the edging or ducking beneath. If that’s the case I plan a change in tactics—a wider no man’s land to thwart above-ground creepers or a deeper edging against the subterranean invaders.

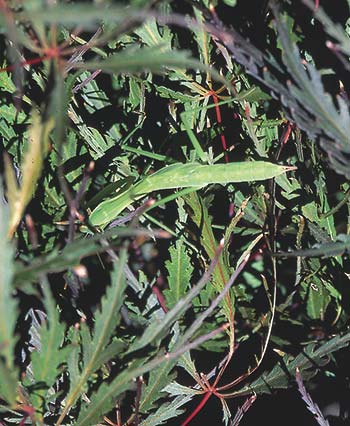

When I have secured the borders, I look to any weeds in the center. Weeds there consist mostly of desirable plants that have run amok. Running root perennials like bee balm, obedient plant, herbaceous artemisias and Japanese anemones have that tendency to spread beyond their appointed places. I sort out such messes by chasing the aggressive plants’ roots outward from their crowns. Sometimes it’s necessary to lift neighboring perennials all around these aggressive species, remove the foreign roots from their crowns and then replace them. Do this now and the oppressed plants will have time to reestablish roots before they stretch upward for the year. No sign of the disruption will remain.

Right: But I will use anything that is free of weeds and can cover the ground, from shredded bark…to the fall leaves shown.

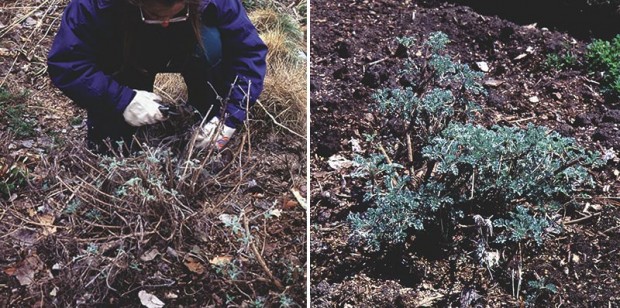

Now or at my next visit in April I divide declining perennials and tend to those who seemed to need help with pests. Dividing is a matter of lifting all of an existing plant, removing the oldest parts—usually the center—and replanting only about one-quarter of the whole. I put back only pieces that are vigorous, outer-edge divisions, as those probably carry the least spores and eggs of pest diseases and insects that may have contributed to the original plant’s decline.

Every plant I lift for dividing represents a loss of organic matter for the bed. So for every bushel of peony, daylily, daisy or anything else I remove, I spread a bushel full of compost on that space and work it into the soil. If I don’t, the area will settle after replanting. Plants in such depressions may suffer from poor air circulation or puddling water.

My final chore in spring is to top up the mulch in the bed. Where the existing blanket of mulch is less than two inches thick, I add new, being careful to leave a clear collar around the crowns of plants so moisture isn’t trapped against stems.

Pre-emergent weed killers are unnecessary if you mulch. Pre-emergent products are often counter-productive in a perennial bed, getting mixed too deep into the soil in the normal course of weeding and dividing so that they do not prevent weeds at the surface, but build up to begin affecting the deeper roots of desirable plants.

There! Now I can sit back and enjoy the season because there will be very little hard work to do until fall!

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.