Part 1 of 2 – Ash replacement trees for root spaces less than 10 feet wide

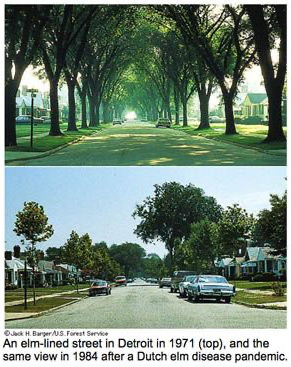

Emerald ash borer has erased millions of native ash trees from our landscapes and forests. It’s hard to believe that similar devastation happened just decades ago, when millions of American elms fell to Dutch elm disease, or that America has also experienced the loss of certain poplars, black locusts and virtually all of its millions of acres of American chestnuts since 1850.

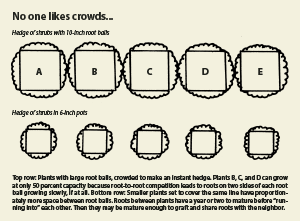

Perhaps we can stop history from repeating itself. After every previous loss, we planted as America always has—in a big way, in masses. As a result, our urban forest is dominated by just a few species, notably various maples, honeylocusts and littleleaf lindens. To protect ourselves from future widespread loss we have to break that pattern and plant a greater diversity of trees around our homes and on our waysides.

Even before the onset of emerald ash borer, concerned arborists had put a moratorium on ash and maple planting and begun planting less common trees. Tree planting became a matter of mixing species within a city block, rather than planting lines of hundreds of the same species, even the same clone of a species. They are making sure that trees won’t in the future be exposed and lost in blocks of hundreds and thousands, as they are now being lost.

For that next epidemic will occur. In this age where materials are whisked from one side of the world to another, complete plant quarantine and protection from new pests is impossible. You can take the same smart step and plant one of many wonderful tree species that are not in the “big three” when you replace that lost ash.

Choose from the following line-up. It’s a catalog sorted by the amount of root space the tree will have to grow in. After looking into all of them, I have an interest in so many that where my family removed 20 dying ashes from a relative’s property, we’ll probably replant with 20 different species from this list!

Trees for spaces where roots can spread just 5 feet wide

These trees can tolerate the restricted root space of small islands and the narrowest strips between sidewalk and street. Some may need pruning to remove lower branches as they grow, creating clearance for traffic below the main branches.

Chinese fringetree (Chionanthus retusus). 15-25’ tall, may be taller. Slow to grow, less than 12” per year. Often shrubby in habit, to attain tree form must have lower limbs removed as it grows. Hardy within the Detroit Metro area but may not be hardy in the colder parts of zone 5 in suburbs. Bright white confetti flowers in June. Blue-black fruit in fall is relished by birds but borne only on female trees, if a male fringetree is nearby. Fall color may be yellow. Grows in full sun or part shade. Prefers deep, moist soil but is very tolerant of a wide range of soil conditions.

Crabapples (Malus varieties with known disease resistance such as ‘Adams,’ ‘Prairifire,’ ‘Red Jewel,’ and ‘Sugar Tyme’). 15’ (‘Red Jewel’), 18’ (‘Sugar Tyme’), 20’ (‘Prairifire’), 24’ (‘Adams’), rounded or slightly narrower than tall. Grows about 12” per year. Flowers white (‘Red Jewel’), pale pink (‘Adams’, ‘Sugar Tyme’) or dark red-purple (‘Prairifire’). Fruit small, red and persisting prettily into and even through winter. Birds eat the fruit in late winter. Full sun, well-drained soil.

Hawthorns (thornless types such as Crataegus phaenopyrum ‘Princeton Sentry,’ Washington hawthorn, and C. crusgalli var. inermis, Crusader hawthorn). 20 to 25’ tall and wide. 12-15” growth per year. White flowers (with unpleasant odor—Crusader) come later than crabapples but help these trees masquerade as crabs. Fall color orange to red or purple. Crusader keeps its small reddish fruit into early winter, ‘Princeton Sentry’ until spring; birds are attracted to both. Full sun and any type of soil so long as it is well-drained.

Japanese tree lilac (Syringa reticulata). 20 to 30’ tall and not quite as wide. Grows 12 to 18” per year. Creamy white, fragrant flowers open in June, weeks after common lilac. No significant fall color but the polished red brown bark brightens a winter day. Full sun. Well-drained soil.

Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa). About 20’ tall and wide, can be larger. Grows about 12” per year. Often sold as a multi-stemmed or very low-branched specimen, but single trunk kousa dogwoods make excellent small shade trees if lower limbs are discouraged or removed. White flowers in June that persist into July. Varieties with pink flowers, larger or later blooms are available. Large rosy fruits favored by birds in late summer. Bark develops polished tricolor effect as the tree ages, very attractive in winter. Fall color may be good maroon. Part shade is best but will tolerate full sun. Moist, well-drained soil.

Redbud (Cercis canadensis). 20 to 30’ tall and wide. Very fast growth when young, slowing to 12 to 18” per year. Flowers are tiny but numerous, red-violet nubs all along the branches in May. Fall color can be a clear yellow. Bark is near-black with crevices revealing orange beneath. Some people object to the shaggy winter look in a year when many seed pods form. Best in half sun or full sun in moist, well-drained soil but is very tolerant of almost all light and soil conditions except soggy soils.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier species). 25’ tall, may be taller; 15-20’ wide. Grows 1-2’ per year. Fragrant white flowers in early May. Edible, sweet, blueberry-sized fruit in midsummer loved by birds. Fall color variable each year, yellow to deep red-orange. Smooth gray bark. Best in sun or half-sun in moist, well-drained soil.

Trees for root spaces between 5 and 10 feet wide:

Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense, fruitless varieties such as ‘Shademaster’ and ‘His Majesty’). 30 to 45’ tall, often broader than tall. Grows 12 to 18” per year. No showy bloom. Brief yellow fall color. Very open crown provides light shade and beauty of line in winter. Handsome corky bark develops in its old age. Full sun. Most soils are okay.

Golden rain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata). 30 to 40’ tall and wide. Grows 1 to 2’ per year to form a round crown of widely spaced branches for light shade. Flowers are large yellow conical clusters in late June, but bloom time is variable from plant to plant; some don’t flower until August. Seed pods are showy, like yellow-green Chinese lanterns draping the tree in bunches. No fall color. Full sun to part sun. Any well-drained soil. Tolerates high alkaline soils, drought and heat.

Hophornbeam or ironwood (Ostrya virginiana). 25 to 40’ tall and wide. Grows 8 to 12” per year. No significant flower or fall color, just a dependable small shade tree. Full sun to half shade. Well-drained soil.

Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus, European; C. caroliniana, American). 40-60’ tall, 30-40’ wide. 8 to 12” growth per year. American hornbeam or musclewood smaller by half and slower to grow than European. Inconspicuous flower. Fall color late, yellow, variable by year. Smooth steel gray bark more or less fluted like a well-muscled, flexed biceps. Best in full sun and well-drained soil.

Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum). 40’ tall, may be taller; variable in width. Blue-green foliage is purple while leafing out, yellow in fall. Grows 1-2’ per year. No significant flower or fruit. Best in rich, moist, well-drained soil in full sun.

Mountain silverbell (Halesia monticola). 60’ tall by about 40’ wide, upright or conical in form. Grows 12-18” per year. White or pale pink bell flowers hang from the branches in May. Fall color is not usually notable. Part sun is best. Moist, well-drained soil.

READ MORE: Replacement options for dying ash trees – Part 2

Article and illustrations by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.