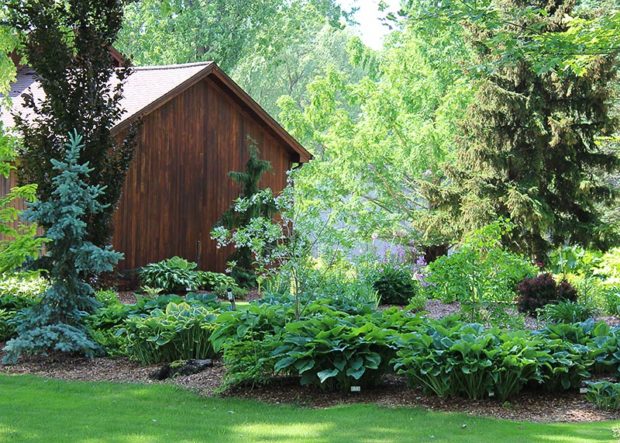

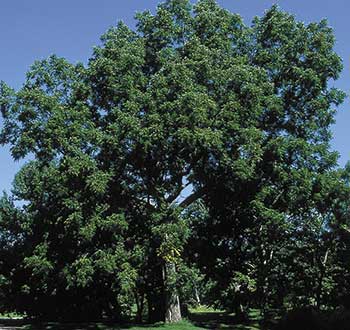

Editor’s Note: The following are bonus photos from a profile of the Greanya and Byler gardens featured in the May 2022 issue of Michigan Gardener. To read the full story, pick up a copy of Michigan Gardener in stores or see it in our Digital Edition, which you can read for free at MichiganGardener.com.

photos by Lisa Steinkopf