My tree peony is almost 3 feet high and about 7 years old. It is healthy and gets about 7 huge fuchsia blooms. Two years ago it sent up a couple of what I assumed were suckers from the root system. I cut them off at ground level. Last year it sent up about a half dozen and I cut all but one off just to see what it amounted to. It did have one tiny pale pink blossom and the leaves appeared to look more like a bush type peony. I’m afraid to let these mature, as it’s taking away from the tree appearance. What exactly are they and how do I deal with them?

Tree peonies are flowering shrubs which grow from 1 to 6 feet tall. The reproduction of tree peonies is mainly done by two methods of vegetative propagation: tuft division and grafting. In the division method, a large plant is simply divided into small plants, each bearing its own roots. In the grafting method, a regular herbaceous peony’s rootstock is used to nourish a tree peony scion until the tree peony produces its own sustaining roots.

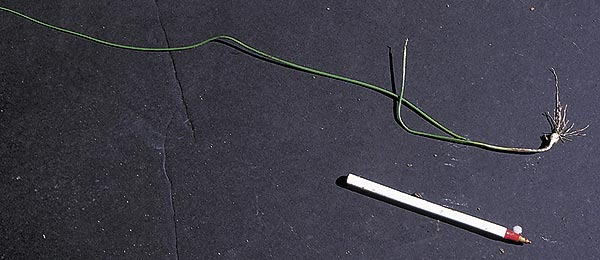

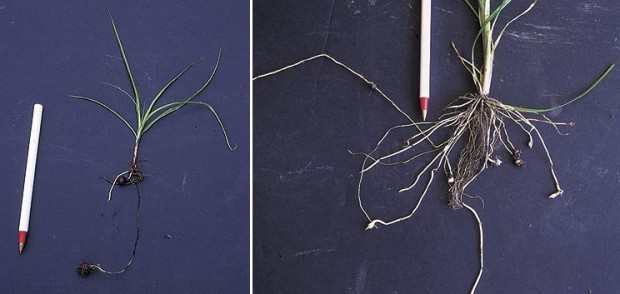

The process of planting a tree peony is similar to planting an herbaceous peony, except for two major differences: Allow 4 to 5 feet for the spacing of tree peony plants and plant the tree peony deeply to permit its own roots to form more rapidly and abundantly. The union of the scion and the rootstock should be at least 5 to 6 inches below ground level. If planted too shallow the herbaceous rootstock will send up shoots of its own, called “suckers.”

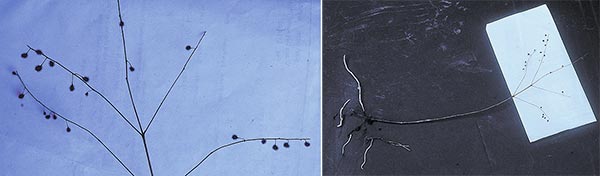

You can tell the difference between a new tree peony shoot and one from the rootstock by the way they look. The foliage is quite different from that of the grafted tree peony. Wait until you are sure these suckers are from the rootstock before removing them as your tree peony will also produce basal shoots and these are what you want. Carefully cut the suckers off, as close to the root as you can.

To really solve the problem, however, as soon as you can tell your tree peony has grown some of its own roots, dig it up in the fall and cut off all the root below the original graft. Keep cutting back suckers, until you can dig the plant. If sucker roots are left to grow for any length of time, they will diminish your tree peony or worse.

Tree peonies are heavy feeders but dislike large doses of fast-acting nitrogen fertilizers. They respond well to a generous, early autumn top dressing of a slow-release organic fertilizer. Its high potash content encourages flowers to develop. A light sprinkling of a general fertilizer can be applied in the spring.

Tree peonies respond well to pruning. You should aim for a broad, multi-stemmed shrub of up to 5 feet in height which will not need staking. Chinese and American types have a naturally branching habit and will need less regular pruning than the Japanese and French types.

In February, just as the growth buds are swelling, trim off all the dead wood. You will often find that the new shoots are coming from lower down the stem, leaving a small dead spur. Whole branches will sometimes die. These should be pruned back to a live bud, or to just above ground level.

With a young plant, only remove dead wood during the first two years to help get the plant established. Don’t be tempted to prune further. After this, if your plant forms a good shape, no regular pruning is needed. However, if your plant has few stems and is poorly shaped, then prune hard. You may see buds at the base of the stem or shoots coming from below the soil. Prune back to these or down to 5 inches or less from the ground. Even if you can’t see any basal buds, adventitious ones will form. The best time to prune is early spring, although this may mean that you sacrifice some flowers in the coming year. You can prune directly after flowering but regrowth is slower.

If you have, or inherit, an older tree peony which has never been pruned, it can be transformed and rejuvenated by applying this same technique. It is best to prune just one main stem each year, cutting it down to about 5 inches. It takes courage to do this, but is usually successful. There’s no need to be concerned about moving even a large, mature tree peony. Just move it during early autumn as you would any other woody deciduous shrub.