by P.J. Baker

If you have quite a bit of shade at your house, everyone says, “Oh, you want hostas. That’s what grows in shade gardens.” Well, if you go out in the woods in Michigan you will find many flowers, but no native hostas. Native to China and Japan, hostas are wonderful shade plants. Used in combination with other shade plants, or using 2 to 3 different hostas together, they can be beautiful.

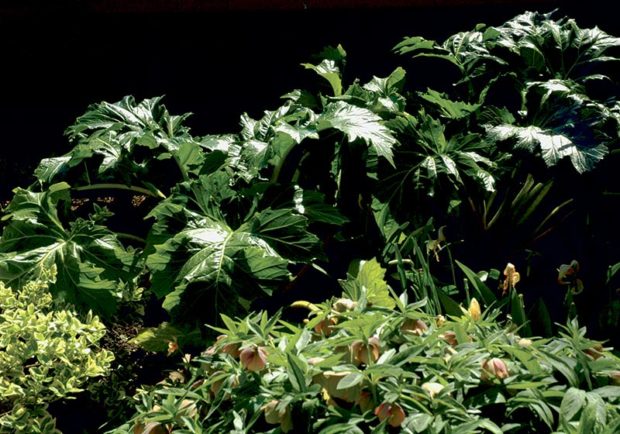

I have a shade garden that is so full I do not have room for anything else. However, there are no hostas—there is no space left to plant them. I have flowers all summer long and interesting foliage when there are no flowers. My hellebore (Lenten rose) starts blooming in March, with or without snow, and it is evergreen. I like it under trees. The only maintenance is cutting off old dead leaves in the spring. Another early bloomer that has variegated foliage is lungwort (Pulmonaria). These have blue and pink flowers in April or May. This groundcover looks great even when not flowering. Note that it can spread easily by seed.

Perennials

Some of my favorite perennials for shade are columbine, astilbe, brunnera, coral bells, foxglove, epimedium, geranium and various ferns. Astilbe flowers at different times and if you get several different hybrids, there can be one blooming most of the summer. Some also have reddish leaves and all have lacy foliage. The flowers of brunnera look like forget-me-nots. Coral bells have many variegated and ruffled edges on their foliage. Geranium likes sun or shade, often has fragrant foliage, and has different bloom times. These perennials are just a few of many that are available.

Grasses

There are also several grasses that can be planted in the shade. This also adds winter interest; the dead flower heads are lovely all winter. Cut most grasses to ground level in the spring. Several grasses for shade are Northern sea oats, tufted hair grass, variegated purple moor grass, Japanese forest grass (Hakonechloa), and many types of sedges. These grasses range in height from 6 inches to 3 feet. The foliage is found in an assortment of colors such as blue, yellow, green, and variegated.

Bulbs

Bulbs for the shade include Spanish bluebell, fritillaria, Italian arum (Arum italicum), dog’s tooth violet or trout lily, winter aconite, and great camas (Camassia leichtlinii). Camassia is a native bulb used by Native Americans for food. For interesting variegated foliage in winter and beautiful orange berries, use the Italian arum. Most of the bulbs bloom in the spring for a lovely early show. Then in late June after the foliage turns yellow, you can plant shade annuals in the area and have an all-summer show.

Annuals

There are many annuals that can be used in the shade besides impatiens and begonia. I like coleus, with its striking foliage, and torenia.

Shrubs

Shrubs are a staple of the garden and there are several that prefer the shade. If you have a protected area on the north or east side of your house, plant broadleaf evergreens. These include rhododendrons, azaleas, kalmias, and euonymus. There are evergreen and deciduous hollies (winterberry) that also have berries for winter interest.

More shade shrubs include fothergilla, summersweet, smooth hydrangea, panicle hydrangea, oakleaf hydrangea, and Virginia sweetspire. Hydrangeas also offer winter interest with their dead flower heads. If needed, the smooth and panicle hydrangeas may be cut down to about 12 inches in the spring. Some offer great fall color. Oakleaf hydrangea turns red in fall, although because of winter injury it may not flower every year; do not cut it down in the spring. Fothergilla turns yellow in fall. Virginia sweetspire is native and turns reddish-purple, often persisting into winter.

I encourage you to study and look around your neighborhood for a summer before you start your shade garden. Put a plan on paper; you will be grateful you spent the time planning your garden. You may decide to include hosta plants, or like me, you may find you ran out of space.