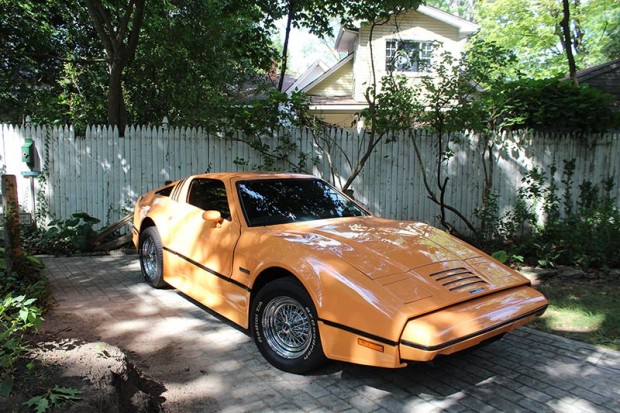

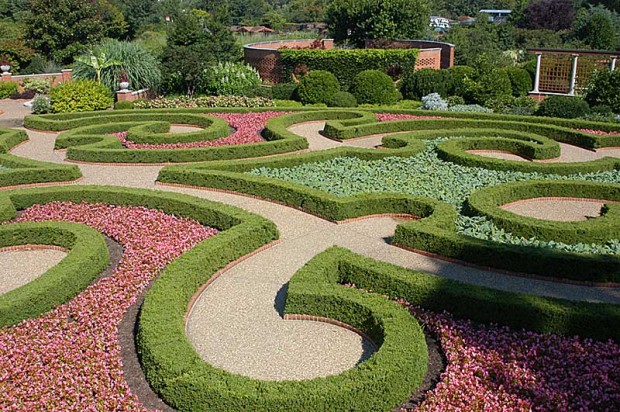

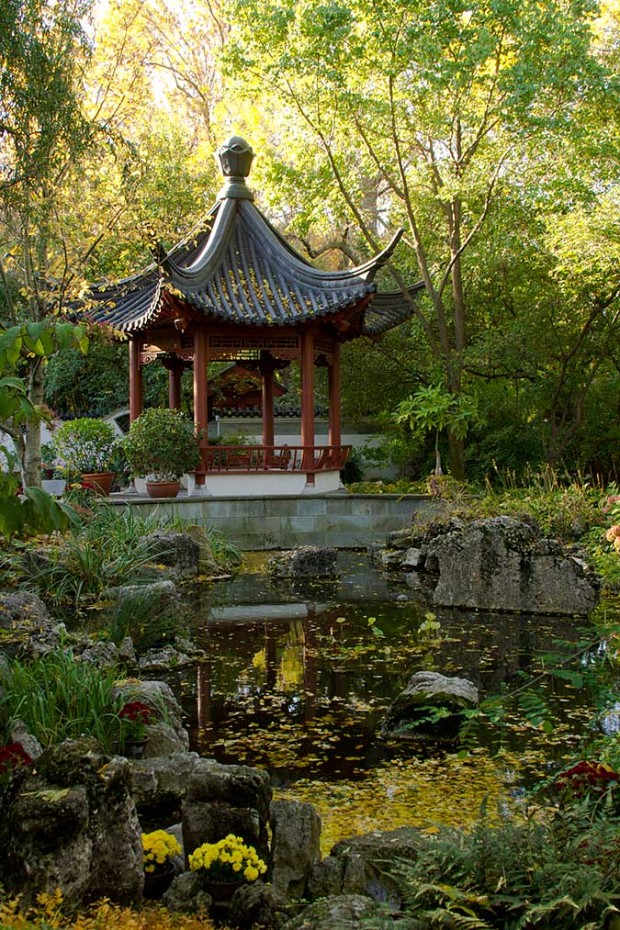

Editor’s Note: The following are bonus photos from a profile of Bob Labadie’s garden featured in the April 2018 issue of Michigan Gardener. To read the full story, pick up a copy of Michigan Gardener in stores or read it in our digital edition, which can be accessed for free on our website home page.