The Country Garden Club of Northville presents its 22nd Annual Northville Garden Walk on Wednesday, July 8, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Six private gardens will be open. Attendees will also enjoy garden/craft vendors at Mill Race Village, complementary homemade cookies and live music. The walk fee is $10 and proceeds support local, state & national non-profit organizations. For more information, visit www.cgcnv.org.

Janet’s Journal: In July, let garden problems slide by

by Janet Macunovich / Photos by Steven Nikkila

In July it can be oppressively humid. As the heat takes its toll and frustration sets in, let’s look at some common summer garden problems.

Holes in hostas are history.

Most of the damage you see in July took place months ago when that foliage was cool and new. As bad as your hostas may look, the condition is far from fatal. The plants have had plenty of time in the sun to photosynthesize all the sugars and starches they need for the year plus sock away the surplus for next spring. In between holes, they still have lots of leaf surface left to keep on banking starches right into fall.

Whatever you do, don’t put out little saucers of beer now, even though it’s true that they will attract and drown slugs. The time to deal with that slug problem is next spring. Then, clear away all the mulch and other plant debris from slug-riddled areas. Leave the soil surface naked and dry. While hostas and other plants are emerging, during the last half of April and first half of May, set out slug traps. Beer traps are fine, but wetted sections of newspaper are at least as good, and they’re far less messy. Just lay them down in the morning near the first hosta shoots, then flip them over before the sun goes down and kill the slugs you find hiding there. They hide there because you took away all the other places where they might have escaped the sun. Dispatching a hundred slugs in April is more productive and far less smelly than drowning a thousand in July.

What goes down will come back up.

Eye-cooling lobelia, pansies, verbena and some other annuals have the habit of opening one last flower on the fourth of July then stretching out to give dirty sweat socks a run for the “Most Ugly” title. They can be made a bit neater in July but will rarely resume blooming until mid- or late August. That’s because it’s too hot at night. So chemicals that would be created within the plant’s cells while it’s cool and dark don’t form. Those chemicals provide the only nudge that can make the plant produce new flowers. Without their chemical cues, the plants sit out July—green, seedy and waiting.

Cut back your heat-stalled annuals now. They’ll grow back over the next month and resume blooming shortly after the heat breaks in August. The first aim of cutting back is to eliminate all the seed pods that are developing—as seed forms, it delays formation of new blooms. The shearing also stimulates new, bushier growth. You can clip so far as to leave only a few inches of stem. Keep the plants well-watered and apply a half strength, water-soluble fertilize after a couple of weeks. Be careful not to overdo the water or fertilizer for plants in a container. Once cut back they have less leaf surface to take up water. They may need less frequent watering than they did in spring since they’re taking longer to use what the pot can hold.

Just close your eyes and smell.

Powdery mildew annoys people out of all proportion to the damage it does to plants. In spring, one kind of mildew fungus or another can and usually does infect the leaves of tall phlox, bee balm, aster, zinnia, perennial sunflower and some other garden plants. During the cool weather the fungi grow slowly within the leaves, which continue to function normally if less vigorously. Then when conditions are right, the fungus finishes its development and covers the leaf with gray spores.

By the time we see gray, the damage is already done. You can try to arrest the mildew’s spread by plucking off all discolored leaves and spraying a fungicide on those that look healthy. Or you can sit back, close your eyes and smell—those sweet-smelling flowers still come, using energy captured by the leaves over more than three months.

Spraying can add fuel to the July fires, though. Whether it’s a purchased fungicide or one made with the baking soda on the kitchen shelf, applying it always carries some risk of burning the crabapple foliage or the leaves of sensitive plants nearby. The chances of causing a chemical burn are much higher when the air is hot and the plant is stressed by drought or heat—July conditions.

Don’t run up a tab for a scabby crab.

Crabapple scab is a fungus that acts much like powdery mildew, infecting early and showing itself late. It’s not unusual for a crabapple that’s susceptible to apple scab to defoliate by August. Its leaves yellow and drop off one by one as the fungus finishes its work. Once again, this is disfiguring but not a threat to the crabapple’s existence. Given an observant resident gardener as a guide, you can find at least one full-sized, regularly-blooming crabapple in every neighborhood that has dropped its leaves early every year for 30 years or more. Even if July’s pressure makes you feel you must do something for a scabby crabapple, all you should do at this point is rake up the diseased foliage and cart it away.

Then, if you still feel anxious about your crabapple next March, you can call a tree care company and sign up to have the tree treated several times with a scab-preventive fungicide, beginning when the leaves first begin to grow. Don’t try it yourself—most home spray equipment is far too small and most crabapples are far too big to be an effective match.

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of the books “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet on her website www.gardenatoz.com.

Plant Focus: Cushion spurge (Euphorbia)

Right: Purple wood spurge (Euphorbia amygdaloides ‘Purpurea’)

by George Papadelis

While English gardeners have prized the merits of cushion spurge (euphorbia) for several years, most American (Michigan) landscapes have yet to benefit from their striking foliage, form, and flowers. Besides poinsettias, the most common American euphorbia is E. polychroma (also called E. epithymoides) whose bright yellow flower bracts in May are followed by an attractive 15-inch clump of pale green foliage. However, several exciting perennial varieties of euphorbias have become more readily available. For a truly stunning display from spring until fall try purple wood spurge (E. amygdaloides ‘Purpurea’). The purple-red new growth is followed by deep green leaves held on sturdy 15-inch stems providing the excellent form for which this genus is so well known. Clusters of chartreuse flowers in spring are an attractive contrast to the foliage. A light winter mulch is recommended but this easy-to-grow plant will tolerate a poor soil and prefers full or partial sun.

For similar striking foliage in your perennial border, E. griffithii ‘Fireglow’ has a much larger growth habit. The pinkish-purple young growth is followed by fiery orange flower bracts in May and June. Sturdy stems support this tidy clump until fall when the foliage ripens to hues of yellow and red. This hardier euphorbia has similar cultural requirements as the aforementioned varieties, but prefers more moisture.

For rock gardens or stone walls, donkey tail spurge (E. myrsinites) is an interesting, low-spreading plant. Stems covered with blue-gray leaves produce contrasting sulfur-yellow flower bracts only 6-inches tall in late spring. Unlike most other euphorbias, this variety tends to be short-lived, but is really worth its life span.

Another euphorbia unjustly underused is an old fashioned annual referred to as snow-on-the-mountain E. marginata. Grown for its showy foliage, lower leaves are a glossy green while upper leaves are white margined. This foliage combines beautifully with brightly colored annuals or can be used as an interesting cut flower. Try the more compact variety ‘Summer Icicle’ which only grows 24-inches tall.

Whether it’s annual or perennial, common or rare, euphorbias deserve a place in your border or rock garden. Please keep in mind that many euphorbias produce a sticky sap that can cause skin irritation.

George Papadelis is the owner of Telly’s Greenhouse in Troy, Shelby Township, and Pontiac, MI.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Eradicated from Three Michigan Counties

According to the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) has been eradicated from three counties across the state: two sites in Macomb County, two sites in Ottawa County, and multiple locations within Emmet County. HWA was first detected in Emmet County in 2006, then at the Macomb and Ottawa county sites in 2010.

According to the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) has been eradicated from three counties across the state: two sites in Macomb County, two sites in Ottawa County, and multiple locations within Emmet County. HWA was first detected in Emmet County in 2006, then at the Macomb and Ottawa county sites in 2010.

The infestations were believed to have originated from hemlock nursery stock originating from HWA-infested areas of the U.S. The infested trees at each site were removed and destroyed. Nearby trees were treated with pesticides and surveyed annually over the course of at least three years.

HWA is a small, aphid-like insect that uses its long, siphoning mouthparts to extract sap from hemlock trees. Native to eastern Asia, HWA was discovered in Virginia in 1951, and has since spread over an area from Georgia to Maine, decimating hemlock stands.

Over 100 million hemlock trees are present in Michigan forests, providing valuable habitat for a diversity of animals, including birds, deer, and fish. These trees are critical to the ecology and aesthetics of Michigan’s northern forests. Michigan law restricts the movement of hemlock into the state, and includes a complete ban on the movement of hemlock from infested areas.

Tree owners are asked to examine their hemlocks for the presence of white, cottony masses on the underside of branches where the needles attach. If you suspect HWA, contact MDARD immediately: email MDA-Info@michigan.gov or call 800-292-3939.

For more information on the HWA quarantine or other exotic pests, go to www.michigan.gov/exoticpests.

Look beyond your vegetable garden—a salad awaits you in the weeds

Watch this fun video featuring foraging expert Wildman Steve Brill touring New York’s Central Park in search of edible common weeds such as Garlic Mustard, Violet, Poor Man’s Pepper, Pennycress, Cattails, and more. Many of these weeds are native to Michigan as well.

Maintaining tree peonies

My tree peony is almost 3 feet high and about 7 years old. It is healthy and gets about 7 huge fuchsia blooms. Two years ago it sent up a couple of what I assumed were suckers from the root system. I cut them off at ground level. Last year it sent up about a half dozen and I cut all but one off just to see what it amounted to. It did have one tiny pale pink blossom and the leaves appeared to look more like a bush type peony. I’m afraid to let these mature, as it’s taking away from the tree appearance. What exactly are they and how do I deal with them?

Tree peonies are flowering shrubs which grow from 1 to 6 feet tall. The reproduction of tree peonies is mainly done by two methods of vegetative propagation: tuft division and grafting. In the division method, a large plant is simply divided into small plants, each bearing its own roots. In the grafting method, a regular herbaceous peony’s rootstock is used to nourish a tree peony scion until the tree peony produces its own sustaining roots.

The process of planting a tree peony is similar to planting an herbaceous peony, except for two major differences: Allow 4 to 5 feet for the spacing of tree peony plants and plant the tree peony deeply to permit its own roots to form more rapidly and abundantly. The union of the scion and the rootstock should be at least 5 to 6 inches below ground level. If planted too shallow the herbaceous rootstock will send up shoots of its own, called “suckers.”

You can tell the difference between a new tree peony shoot and one from the rootstock by the way they look. The foliage is quite different from that of the grafted tree peony. Wait until you are sure these suckers are from the rootstock before removing them as your tree peony will also produce basal shoots and these are what you want. Carefully cut the suckers off, as close to the root as you can.

To really solve the problem, however, as soon as you can tell your tree peony has grown some of its own roots, dig it up in the fall and cut off all the root below the original graft. Keep cutting back suckers, until you can dig the plant. If sucker roots are left to grow for any length of time, they will diminish your tree peony or worse.

Tree peonies are heavy feeders but dislike large doses of fast-acting nitrogen fertilizers. They respond well to a generous, early autumn top dressing of a slow-release organic fertilizer. Its high potash content encourages flowers to develop. A light sprinkling of a general fertilizer can be applied in the spring.

Tree peonies respond well to pruning. You should aim for a broad, multi-stemmed shrub of up to 5 feet in height which will not need staking. Chinese and American types have a naturally branching habit and will need less regular pruning than the Japanese and French types.

In February, just as the growth buds are swelling, trim off all the dead wood. You will often find that the new shoots are coming from lower down the stem, leaving a small dead spur. Whole branches will sometimes die. These should be pruned back to a live bud, or to just above ground level.

With a young plant, only remove dead wood during the first two years to help get the plant established. Don’t be tempted to prune further. After this, if your plant forms a good shape, no regular pruning is needed. However, if your plant has few stems and is poorly shaped, then prune hard. You may see buds at the base of the stem or shoots coming from below the soil. Prune back to these or down to 5 inches or less from the ground. Even if you can’t see any basal buds, adventitious ones will form. The best time to prune is early spring, although this may mean that you sacrifice some flowers in the coming year. You can prune directly after flowering but regrowth is slower.

If you have, or inherit, an older tree peony which has never been pruned, it can be transformed and rejuvenated by applying this same technique. It is best to prune just one main stem each year, cutting it down to about 5 inches. It takes courage to do this, but is usually successful. There’s no need to be concerned about moving even a large, mature tree peony. Just move it during early autumn as you would any other woody deciduous shrub.

MSU Expert may have found a cause for honeybee loss

The Detroit News:

A Michigan State University researcher may have found the key to the infiltration and destruction of the nation’s honeybee colonies.

It has to do with the invader’s stink. Specifically, the now-infamous Varroa mite uses a chemical camouflage to match its body odor — or something close to it — to its honeybee host. It even fine-tunes the formula to mimic the subtle differences of smell among bees in individual colonies.

“Honeybees rely a lot of on chemical communications,” said Zachary Huang, an MSU entomologist and lead author on a paper in the academic journal, Biology Letters, explaining the mite’s ability to deceive.

Janet’s Journal: Eye to Eye With the Worst of the Garden Weeds

Here’s an intelligence report on some of the most persistent and sneakiest garden weeds of Michigan gardens. To pack the most information into available space, we’ll let pictures and vital statistics do the talking.

Most Persistent

Bindweed, Canada thistle, Ground ivy, Mexican bamboo,

Nut sedge, Scouring rush, Violets, and Wild garlic

These are some of the warriors you’ll have to kill and kill again. They are weeds that cause people to shake their heads even as I answer their question, “How do I get rid of…” The gardener may even smile ruefully while saying over and over, “No, I’ve tried that.”

If you’ve battled these and been beaten, I don’t doubt you’ve tried, but I do doubt that you understood and matched the persistence of your foe. Cut off their heads—their green, leafy source of energy—and they sprout anew from deep, extensive root systems like the mythical beast which sprouted two heads each time one was cut. Each cutting, digging or herbicide application by the gardener puts a drain on the roots’ starch reserves, but each day a new shoot gathers sun, it replenishes those roots. If you attack just once, twice or three times a year and let the survivors surface and gather sun for weeks or months during the cease-fires, you insure a perpetual war.

To best the beasts on this list, beat them at their own game. After you roust out every bit of green and as much root as you can reach, post a guard. Expect new shoots within a week. Find them and cut them before they can return to the root the starch they used in reaching the sun. Be vigilant in this follow up and you will gradually exhaust the weed’s reserves.

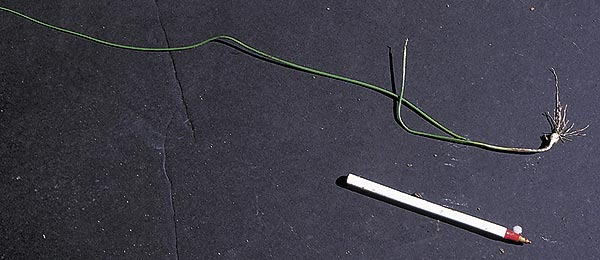

Wild Garlic

Wild garlic (Allium vineale), which hides its narrow foliage among grass blades, can always be identified by its smell. Survives mowing as well as grass, escapes broadleaf weed killers, and stores enough energy in the bulb to return repeatedly if weeders leave the bulb behind. Infestations are usually best handled by killing or digging out all vegetation in the area and then maintaining a thick mulch and a weeding vigil for 18 months.

Mexican bamboo

Mexican bamboo, Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum). Perennial, up to 9 feet tall, spreading far and wide from established clumps by stout underground runners (left). Jointed, hollow stems explain the common name “bamboo.” The center section of stem has been eliminated in this photo for clarity’s sake. Grub out the roots or apply Roundup and be prepared to kill remnant sprouts for a season or two.

Canada thistle

Perennial, wickedly persistent Canada thistle—Cirsium arvense, which is not native, despite its common name. A stem and a basal clump are shown here, left of the glove. Note the running roots, which can persist and keep sprouting even through a year or two of frequent pulling or spraying with herbicide. The key to control is to be even more persistent than the plant and to adopt as a mantra what Edwin Spencer writes in All About Weeds, “…any plant can be killed—starved to death—if it is not permitted to spread its leaves for more than a few days at a time.” The annual prickly sow thistle (Sonchus aspera), immediately right of the glove, and biennial bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare), far right, are weedy but not nearly so much trouble to eliminate. Just keep pulling or cutting the annual and biennial thistles before they set seed, and keep the area well mulched to prevent existing seed in the soil from sprouting.

Violet

Violet, common blue violet (Viola sororia). Perennial, often tolerated in gardens for its blue-violet flowers in spring, yet hated for colonizing nearby lawn. A typically schizophrenic approach by gardeners! Either accept it in both places or eliminate it from both. Like ground ivy, it can be killed in lawns with broadleaf weed killer—may take repeated applications—but will then return from seed if the grass is not pampered until thick enough to shade out the seedlings.

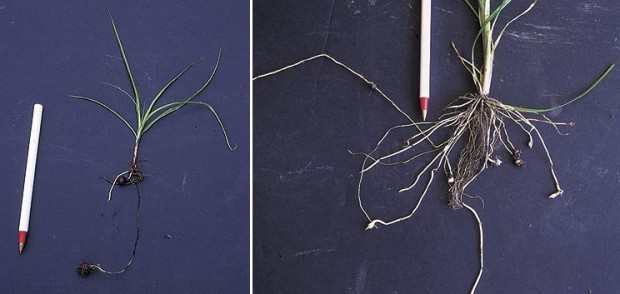

Nut Sedge

Perennial nut sedge or yellow nutgrass (Cyperus esculentus) infuriates gardeners by returning even if pulled and pulled again. But of course it returns if the soil is not loosened deep and well so that the brown nut-like tubers come out, too. In the inset photo, note the horizontally-running root, which turns up to produce a second clump of “grass” and the new crop of nuts developing as white bulbs at root tips. Nuts can rest dormant for many years in the soil and be revived by deep excavations. Frightening to think nut sedge tubers are edible and somewhere a large-tuber form may be in development as a food crop!

Ground ivy

Ground ivy

Ground ivy, also called gill-over-the-ground, is Glechoma hederacea, a perennial. It snakes through lawn, rooting where its stems make contact with bare soil. In gardens, freed from a mower’s restraint, it explodes to become a dense mat and can weave its way 18 inches up into stems of other plants. Shallow-rooted, it’s easily pried loose from beds and mulch will prevent it from reestablishing by seed. However, it must also be banned from adjacent lawns. The broadleaf weed killer Trimec will kill it, but the lawn must then be overseeded and thickened by better care lest ground ivy seed simply sprout and re-take the bare soil between grass plants. Sometimes confused with henbit, an annual.

Scouring rush

Field horsetail, or scouring rush (Equisetum arvense), is a native perennial often brought into gardens in tree and shrub root balls. Easiest to eradicate if caught early in its tenure on a property, otherwise it must be dug and surviving pieces starved by repeated pulling.

Bindweed flower

The trouble with focusing on flowers for identification is that the worst weeds—long-lived perennials that are slow to begin blooming—can become entrenched before we know what we’re facing. Once great bindweed (Convolvulus sepium) is large enough to show its two-inch white or pinkish flowers, it’s so well-grounded that its removal will require a two- to

three-year pitched battle.

Bindweed

Convolvulus sepium, the great bindweed (pictured) and its smaller-flowered, smaller-leaved, lower reaching cousin C. arvensis, small-flowered bindweed. Perennial. Extensive, deep, easily broken root systems. My own experience mirrors that of W. C. Muenscher who writes in the textbook Weeds, “Clean cultivation…if performed thoroughly, will control bindweed in two years. The land must be kept black, that is no green shoots should be allowed to appear above ground. Cultivation should be at frequent intervals of about six days. Under certain conditions this time may be extended a few days and under other conditions it may have to be shortened to three- or four-day intervals.

Sneakiest

Enchanter’s nightshade, Glossy buckthorn,

Pokeweed, and Yellow wood sorrel

These weeds earned places on this list by their tendency to present a false face or ride in on invited guests. Once their true natures and their avenues of entry into a garden are known, they are relatively easy to eradicate with informed pulling and thorough mulching.

Pokeweed

Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) is an impressive, statuesque plant draped in purple-black berries in fall. Birds love this native fruit – although it is quite toxic to humans – but gardeners wish their feathered friends would eat all of the berries before they fall and then not excrete any! This photo shows the berries of an established plant – up to 9 feet tall and wide – and the roots of seedlings just 4 months old (center) and one month old (right). The roots don’t run but they do delve deep, so pull them early or be prepared to dig deep.

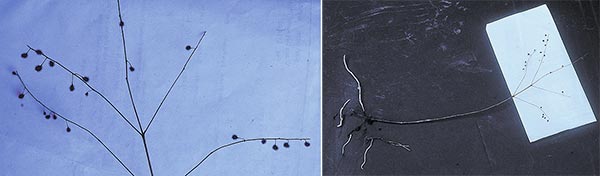

Enchanter’s nightshade

The native perennial, enchanter’s nightshade (Circaea canadensis) is rarely seen in sunny gardens but can drive a shady gardener wild, especially when the buried seeds ripen (right photo). In seed, it seems to pull out easily and completely, but careful loosening of the soil before pulling will reveal the new, white, nearly-detached perennial roots (left photo) which can lie quietly until the next spring.

Glossy buckthorn

Glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) is a small tree with very bad habits. It leafs out early in spring and keeps its leaves far into fall, effectively shading out native plants wherever it sprouts. Since it can thrive in woods, sun, wet areas and dry, it’s a serious threat to native ecosystems of all kinds, as well as gardens. The seeds don’t travel far on their own. Birds eat and then drop them where they roost so the trees are common along fence lines. Fast growing, the gardener must patrol for and pull them at least once a year, and try to locate and remove the mature plants which are providing the shiny black berries. One thing gardeners can be thankful for is the plant’s shallow, fibrous root system – far easier to pull than other woody weeds such as mulberry and tree of heaven.

Yellow wood sorrel & Common wood sorrel

Yellow wood sorrel & Common wood sorrel

Yellow wood sorrel, right, (Oxalis europaea) seems frail and easy to pull, compared to its ground-hugging cousin, common wood sorrel, below, (Oxalis stricta). But like enchanter’s nightshade, the yellow wood sorrel has a deceptive root system. Pull it and it seems to come up easily, roots and all. Yet if one loosens the soil well before pulling and uses a light touch, it becomes clear how many fragile, white, running perennial roots can be left behind by the uninformed gardener. Far easier to deal with is the common wood sorrel, which does not spread below ground but only above where stems sit on moist soil and root (the pen points to such a stem).

Website Extra: Plants, nature, learning at Matthaei Botanical Gardens

Editors Note: The following are bonus photos from a story on Matthaei Botanical Gardens featured in the June issue of Michigan Gardener. To read the full story, pickup a copy of Michigan Gardener in stores now or read it in our digital edition.

A visit to Matthaei Botanical Gardens in Ann Arbor

will leave you inspired and enriched

All photos by Sandie Parrott

Preview: Gardening and life lessons

A Detroit horticulture program is making a difference in the lives of its students

The upcoming June issue of Michigan Gardener (in stores Tuesday, June 2) contains an article about Detroit Pubic Schools’ Drew Horticulture Program. The article is written by Michael Craig, a Detroit Public School special education teacher and horticulture program instructor at the Charles Drew Transition Center. Craig was recently honored with the Michigan Lottery/WXYZ’s “Excellence in Education” Award. Here is an excerpt from Craig’s article:

I am excited to relay to you the story of The Drew Horticulture Program featuring The Gardens at Drew, and in the process, include tips and techniques from our program that you can implement in your own gardens. I’ll also explain how we battled and defeated the dreaded blossom end rot on our precious tomatoes.

The Charles Drew Transition Center, a Detroit Public School, is a unique post-secondary vocational center for the moderate and severely cognitively impaired, visually impaired, hearing impaired, physically impaired, and students with autism. The Transition Center, which serves special education students ages 18-26, is a one-of-a kind educational facility where students have access to an age-appropriate learning environment. The staff develops programs teaching vocational work skills leading to the possibility of employment, providing functional independence and full inclusion into community life.

Read the rest of the story on June 2. Pickup a copy of in stores or read our digital edition.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- …

- 43

- Next Page »