Understand your soil and plants roots to help your plants thrive

By Janet Macunovich / Photos by Steven Nikkila

The hazy, hot eye of summer is upon the garden. Reach for the hose, but use your head for proper watering.

Herbaceous plants—annuals, perennials, vegetables, etc., that have no wood to hold them up—are simply columns of fluids. Roughly 95 percent water, they stand because liquid pressure holds their cell walls taught. Remove much and they fold. Wilted plants might recover with watering, but damage is done during the wilt: from localized scarring of tissues and greater susceptibility to diseases that can enter through weakened tissue to the more general stunting that occurs because the plant was not able to photosynthesize while dehydrated.

Photosynthesizing is the harnessing of solar energy to make food. Plants use sunlight to split water and carbon dioxide molecules in their leaf cells, then recombine those ions with pinches of mineral matter to make sugars, starches, cell thickeners, new cells and everything else they need. Sunlight is the fuel, but water is the main ingredient, lubricant, coolant and transportation device in these leafy factories. Water’s atoms become part of the product, but water also keeps all parts supple and cool enough to work and is the conveyer belt which brings ingredients together and moves finished products from leaf to stem and root. In brighter light and warmer air, the plant factory works faster and more water is needed to keep it running.

No wonder plants ask for water every time we turn around in summer. The best thing we can do in July is to water wisely, not by rote but using a variety of methods geared to specific plants, soil and weather.

specific water requirements.

Take the standard rule, to give plants one inch of water per week. Some of us set out rain gauges to measure rainfall, then turn on sprinklers as needed to top up to that one inch mark. Others read cumulative precipitation in newspaper weather charts and drag out hoses when rain doesn’t add up. Both are smart practices, better than setting an automatic system to run every day or two, rain or shine. Yet you can water even smarter.

One inch per week is an average, but all plants aren’t average. Some need more because their leaves lose more water to evaporation, or when they’re ripening fruits, or if they were cut back and must fluff out all new foliage. Big, thin leaves may lose so much water through evaporation on a hot, sunny day that the roots can’t keep up even if a hose drips there constantly. As an example, look at a ligularia wilted into a green puddle. Many ligularia plants suffer from root rot in summer too, overwatered by a gardener who reaches for the hose every time the plant wilts. The soil becomes super saturated and airless, so they die of starvation and rot.

Some plants need less water than others on a hot or blustery day. Gray, furry or needle-like leaves are designed for minimal water loss. Hairs that make a leaf gray or furry form a layer around the leaf that prevents immediate evaporation or blow-drying of water vapor emerging from pores. The vapor is trapped and sheltered inside the fuzz where it can linger and do its job as a coolant. To grow a gray leaf plant like lamb’s ear (Stachys lanata) next to a wilter like ligularia, water very carefully, feeling for moisture in the soil at the base of each plant before turning the hose on just one plant or the other.

The amount of water available to roots isn’t based solely on amount of water poured onto the soil—that inch we measure in a rain gauge or in a wide-mouth container set on the ground under a sprinkler. Whether an inch will mean there’s enough, too little or too much water for the roots varies with type of soil, drainage, air temperature and wind.

Sandy soil has large pores—spaces too big to hold water up against the pull of gravity. Water runs through sand more quickly than through the tiny pores in clay or loam. An inch of water applied all at once to sand may be gone in a day, though in clay it would have lingered at root tips for a week or more. So sand often needs more than an inch of water per week, meted out by the quarter- or half-inch every few days. Sand’s ability to hold water can be improved by topping it with evaporation-suppressing mulch and mixing into it a generous layer of organic matter or pre-moistened water-absorbent polymers (sold as “Water Sorb,” “Soil Moist,” etc.). These materials can absorb and only gradually lose up to 100 times their own weight in water. Yet even fortified this way, a sandy soil will dry more quickly than clay.

Drainage is the movement of water and air through soil pores. Some soils drain quickly, others slowly. Often the drainage depends on the type of soil well below the surface, so even a sand may drain slowly enough that moss grows on its surface. The only sure way to know how long water lingers in a soil, and how soon life-giving air is also back in the soil after a drenching rain, is to dig a hole 3 to 4 inches deep and touch the soil. What feels cool is damp, but aerated. What feels warm or hot is dry. Soil that actually wets the fingertip is still draining.

Doing touch tests can be revelatory.

Even within a city lot with homogenous soil, some spots will dry more quickly than others. South-facing slopes and elevated areas may be dry while soil a few feet away is still moist, since ground tipped to the sun is often warmer and elevated sites catch more breeze and lose more water to evaporation. Dry spots in lawn or garden often show in early spring as dead patches or where one group of plants is slow to emerge.

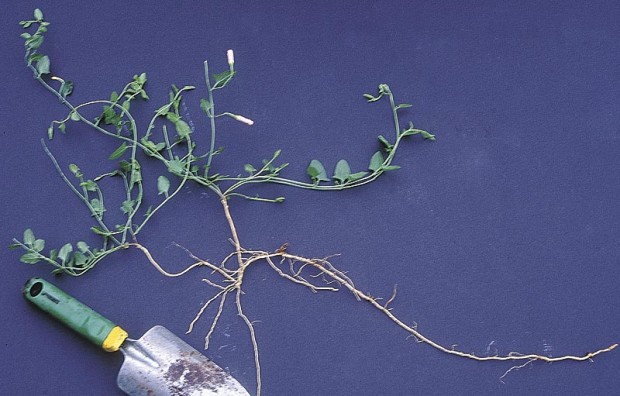

We’re also taught to water gardens less often but more deeply so soil is thoroughly wetted, and probably have been told that watering lightly is bad practice since it “brings roots to the surface.” It’s wrong to think of roots “coming to” anything, but even some of the most scholarly horticultural texts use this phrase that misleads gardeners. As Dr. Joe Vargas of Michigan State University once said in a lecture on watering turfgrass, “I’ve looked at a lot of roots very closely, even dissected them, and one thing I’ve never found is a brain. They don’t know where water is. They can’t sniff it out, either.”

Roots grow if the soil around them is moist enough to supply water and nutrients needed to fuel cell division. They don’t grow if soil around them is too dry. Roots in a dry pocket or dry layer will not move toward moisture.

One thing we learn once we know that roots can’t seek out moisture is that root balls of new plants need special attention. A peat-based root ball of a container-grown plant may dry out far more quickly than the garden loam or clay around it. Roots within the peat will simply stop growing. Until a new transplant’s roots have grown beyond the peat and into the garden soil, its root ball has to be checked separately for dryness even if the soil around it is wet.

Another corollary of “roots can’t go to water” is that although it may be best when sprinkling many flowers, trees and shrubs to water deeply so that the whole depth of the root mass is wetted, plants with shallower roots need frequent, light watering. Lawn roots shorten in summer heat so a daily application of 1/8 inch of water is better than a weekly watering that means days-long drought in the surface layers. Annual impatiens evolved in rich leaf litter in damp jungles, and have shallow roots too. Water them often, but don’t waste water by applying enough to wet the deeper soil layers every time.

Another thing we hear often is that we should water early in the day, not in the evening, so leaves can dry off before night and be less susceptible to disease. This makes sense, reducing the amount of time that fungus-prone leaves are covered in fungus-promoting films of water, but then how does Mother Nature get away with evening and nighttime watering? Thunderstorms and rain showers come when they will, yet the normal state of being for plants in the wild is one of good health—maybe a bit of fungus here and there, but life-threatening epidemics as seen in rose gardens are rare.

If water is applied deeply and occasionally to supplement rain—perhaps weekly or bi-weekly—time of day is not so critical as in an every-day automatic system. Occasional watering means occasional openings for fungus infection. Daily late-day watering increases the chances of fungus infection by a factor of seven or more.

For some plants, an increased chance of fungus infection may be offset by water’s cooling effect. As temperatures rise into the 90s, many plants stop photosynthesizing because their root systems can’t supply enough water to keep that process running at the high speed engendered by high heat. Pores in the leaf close, shutting off the upward flow of water like a drain plug in reverse. Without water flow, photosynthesis can’t take place, and the plant can’t produce fresh sugars to fuel its life processes. It lives off its reserve starches until the air cools. Dr. Vargas’ ground-breaking studies of turf irrigation clearly show that watering during the hottest part of the day is best for lawns because it cools the air around the grass, allowing it to continue to photosynthesize.

Other plants are more susceptible to fungus when exposed to drought or alternating wet and dry. If bee balm (Monarda didyma) that thrives in constantly moist soil is kept dry, its chances of developing powdery mildew are greater. Likewise, lungwort (Pulmonaria species) grown with drought-tolerant bigleaf forget-me-not (Brunnera macrophylla) in the dry shade is more likely to develop mildew than if grown in a constantly moist, well-drained hosta bed.

How about all the hype for weeper hoses and trickle irrigation, to conserve water and keep the leaves from ever getting wet? Does it sound like the only good way to deliver water? With weeper hoses, we often see increased spider mite damage. Regular rinsing keeps mites in check. Roadside plants struggling with pore blockage and light reduction under a layer of grime become more susceptible to pests unless rinsed regularly.

If all this seems too much to keep straight, maybe you haven’t been watered well! Why not go sit in the shade, have a cool drink and think about it? You may see that only one or two of the situations I’ve described here apply to your garden. While the heat’s on and your plants need it the most, fine tune that watering system!

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of the books “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet on her website www.gardenatoz.com.