With apologies to Mitch Albom and thanks to Mike Bosnich…

On the day she died, Diane was working on her rain garden. She had become known in the neighborhood as ‘the woman digging the ditch.’ The small children of the neighborhood had told her this. Little kids liked her. To them, she wasn’t the woman digging the ditch but “the lady with the flowers.”

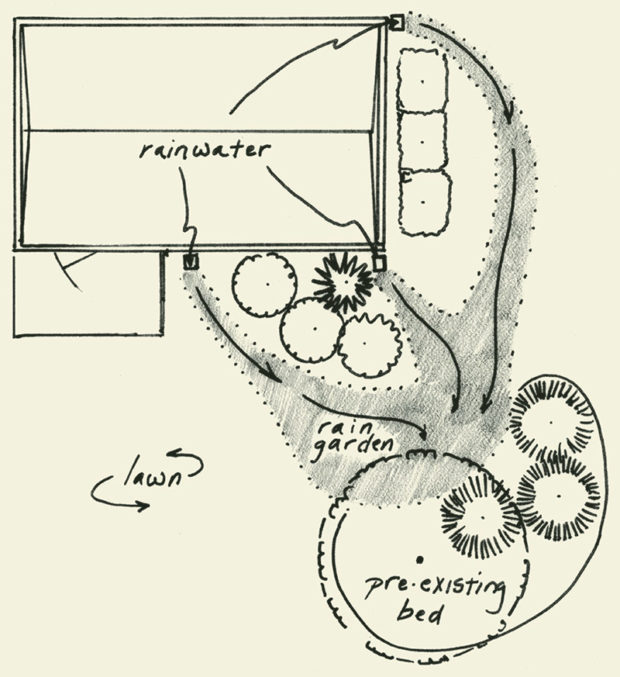

She dug, week by week for over a year, not a ditch, but depressed channels beginning at downspouts then joining, sloping and widening toward the wet area. She disconnected the downspouts from plastic drain tiles that had emptied into the storm drain. Now, rainwater from the roof coursed along the route she’d chosen and settled into that low space.

She’d planted tiny divisions of wetland plants there, and retained the edge of the sunken area with rough cedar logs and fieldstone. She was almost done, the day she died.

It came quickly. An aneurysm, they’d tell her husband.

What she knew was being very tired suddenly, and sitting down at the edge of the rain garden, thinking of salamanders. Light flashed. She closed her eyes.

She opened them to see the oak.

Selma’s massive white oak. Someone who knew trees had guessed it was 400 years old when Selma and her husband built their house nearby.

Shaking her head as if to clear a mirage, Diane stood. Under her feet she found not her rain garden but Selma’s patio. As she looked out across the big yard to the huge tree, a soft rumble filled her head, then sorted itself into words.

“You’ve come. I’ve waited for you.”

“Who…? What…?” she wondered.

“Me. You call me oak. We were acquainted. After I died I was given the job of waiting here until you died.”

“You died? Oh, what a shame… Wait. I died?”

“We died. Don’t be alarmed. You just need time to see it. My death took much longer than yours. I was given more time to prepare. Now, we’re both here and I can tell you about how you killed me.”

“I killed you? No! I helped Selma save you!”

“You had good intentions. I knew that. Now, I must tell you how it came out, and introduce you to others you affected. Sit. Listen.”

She sat.

“I grew in this good place a long time, and was still growing,” rumbled the oak. “People camped. Collected my nuts to grind into meal. Happy people, singers. With many children. They came and went, carrying their homes with them.”

“Indians?” Diane wondered.

“I suppose. Hunters. Fishers. They stopped coming when the farmers came. The farmers rested horses beneath my branches, and plowed above my roots.”

“Then, machines came. They tore down into my roots, there where you are sitting. They crushed the ground between us, heaped soil over my roots, and packed it down. You told Selma to help me.”

“Yes!”

“She did, with water and by loosening that soil. But it took many seasons to grow those roots that were taken from me, and other ones died when they could not breathe. I would have needed many, many seasons to heal.”

“I told Selma to put mulch under you, to get rid of the grass. You were looking better!”

“Yes, at first. You told her also that she could plant bulbs. Spring bulbs, you said, that could bloom each year before my new leaves came. They were very pretty flowers. They didn’t mean to kill me, any more than you did.”

“But how…”

“Selma got older, slower. She wanted more bulbs but thought she couldn’t plant them herself. She hired people. They planted bigger, fancier flowers, more every year. They used drills to make holes. They cut more roots each time. I couldn’t keep up.”

“I’m so sorry.”

“It happens. But look—I’m here, but also still there.”

“There? That other house?”

“Selma’s children. They sent me to a mill, and built a house, a table, a stairway of me.”

“Why tell me this?

“Because that’s how it works. We leave there, we come here, we look at how we are all connected.”

“I never meant…”

“I know. But now you see how things add up. I learned too. About smaller trees I shaded out, squirrels I nourished, small children who fell from my branches.”

“Now,” said the oak, “you must meet the others.”

“Others? Wait…”

But the light dimmed, and she was back where she’d died, in her rain garden.

She was standing and looking toward the neighbor’s.

“Come here!” sang a merry chorus. She saw a cluster of cheery white strawberry flowers, each canted toward her.

“So glad to see you, so glad to say thank you,” they trilled.

“For what?” she asked, stepping toward them.

“For water! Yes! For chicken manure! Oh, yes!” They appeared to be calling and answering, a song in two parts.

“But you’re not in my garden,” Diane said, crouching to watch them more closely.

“No, but we’re downhill, aren’t we?!” they said. “You left the water on. It rolled down the lawn, where it’s packed so hard. It came to us cool, and loaded with the fertilizer you spread there!”

“Well, I’ll be…” she said, looking toward her own home and noticing for the first time the slight uphill grade from the strawberry bed to her house.

“The kids came to see us, we gave them fruit. Then chipmunks, rabbits, and groundhogs. It was a party!”

“It was?” she wondered. “It isn’t any more?”

“Nothing lasts forever,” the sweet voices answered. “That channel intercepts the water now. We’ve moved on!”

“Am I supposed to learn from that? That you grew because of my sprinkler, and then I stopped it by making the rain garden?”

“Yes, learn that it happened. That things flow downhill,” they called in close harmony.

“Well, thank you for telling me,” she said.

“Are you done, then?” came another chorus, thinner and more raspy.

Diane looked toward the sound, to see a throng of astilbe. Droopy, singed, thin astilbe. “Oh, she said. What happened to you?”

“We dried up,” was the crackling reply. “Because Ralph did well!”

The plants’ leaves suddenly formed pointing arms. Diane looked that way to see a lush, glossy, deep green astilbe on the far edge of the strawberry bed.

“I didn’t want any trouble,” Ralph cried. “I never asked for your water and fertilizer!”

“Oh,” she said. “You too?”

“Yes, me too. I kept getting it even when the strawberries were cut off, since I’m ahead of your ditch. But my brother, Shelby, on the other side of this crabapple, didn’t.”

Diane stopped, looking at that group of scorched astilbe. Their rustling movement became a blur. The sound changed.

She looked up, into blue green leaves riffled by wind, and around at striped gray bark. At a thicket of some kind.

The riffle changed tone. It became applause.

Voices joined in. “Thank you! Brava!”

“You’re welcome,” she replied, of lifelong habit. “But, I’m sorry. I don’t know who you are. Where we are. What you are happy about.”

“Serrrrrrrr-viceberry,” the leaves said, sliding against each other. And some giggled. “You gave us this place, all this room to grow, and the ticklish feeling of these birds in our branches every summer.”

“Are you sure?” she asked, looking through the foliage to a field, a rise and a dip, and a far horizon of dark water. “I don’t think I’ve ever been here.”

“Maybe not, but the man with one leg was. You knew him. You talked, and he let us grow.”

The voices waited then, murmuring just a little among themselves. Diane looked down, thinking.

“There was a man, I saw him at the doctor’s a few times. That man?”

Applause again. “That man! You told him he could manage. Not to sell his family’s farm and move in with his daughter. He could. He did. He stopped mowing out here, though. And we grew.”

“So this thanks is for saying encouraging things, polite conversation?”

Laughter, light, louder, then light again, brushed back and forth through the branches. “You see! Everything we do, matters. Thank you!”

“You’re welcome,” she said, looking toward the distant water. “Hey, maybe I have been here! Is that Lake Superior? Are we in the U.P.?”

She looked back to the serviceberries, and started. They were gone. Her nose was just inches from a fence.

She began to step back. A whisper came through the spaces between the wood slats. “Wait. I need to say thanks.”

She paused, looking through the opening. Twigs scratched across the gap. “Are you on the other side of the fence?” she wondered.

“Yes. Thank you for the air,” was the scratchy response. “You told them to give us a fence that lets air through.”

“I can’t think who you mean, or which fence this is,” she apologized.

“You talked in line, at a store. They were putting up a privacy fence. You told them plants do better if there’s air. They hadn’t thought of that.”

“Well, you’re welcome,” she said, bewildered. “Can I ask a question?”

“Oh, please do!” tapped the twigs.

“First, can I see you better?”

“Certainly!” came the scritchy answer. “There’s a gate there.”

In the gateway, she froze. She saw her childhood home, its property line planted with lilac. “I told people about a fence, and those people were living in the house where I grew up?”

“Small world, isn’t it?” tapped the lilacs.

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.