My friend Curt grew up on a “hard scrabble” farm in Kentucky early in the last century, an inquisitive boy who enjoyed the company of older farmers who repaid the interest by teaching him many old and secret ways. Agricultural college and then a degree and career in engineering put a fine edge on all he’d learned. When he said to me one day late in his life, “Janet, I think I’ve figured it out,” I took my notebook from my pocket in anticipation of revelation. What he said, in proof of a key tenet of Murphology known as Groya’s Law, was “I have looked and studied all these years and now I know I am never going to have any good idea what’s going on in this garden!” by Janet Macunovich

My friend Curt grew up on a “hard scrabble” farm in Kentucky early in the last century, an inquisitive boy who enjoyed the company of older farmers who repaid the interest by teaching him many old and secret ways. Agricultural college and then a degree and career in engineering put a fine edge on all he’d learned. When he said to me one day late in his life, “Janet, I think I’ve figured it out,” I took my notebook from my pocket in anticipation of revelation. What he said, in proof of a key tenet of Murphology known as Groya’s Law, was “I have looked and studied all these years and now I know I am never going to have any good idea what’s going on in this garden!” by Janet Macunovich

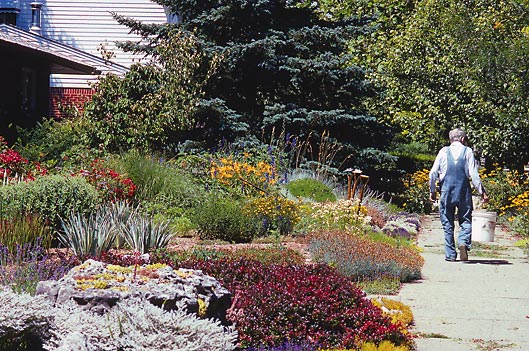

Photographs by Steven Nikkila

30 years ago, writer Arthur Bloch presented us with Murphy’s Law and a collection of other undeniable ironies. I’m basically an optimist and an opportunist, even a follower of philosophies such as “open your mind and the universe will provide.” Yet I found myself smiling wryly and even agreeing with what Bloch assembled to advance that basic tenet, “If anything can go wrong, it will.”

Over the years bits from that book would come back to me as I gardened. Situations I encountered while digging, planting or designing would strike me as spin-offs from Murphy’s Law and I would think, “There should be Murphy’s Laws of Gardening.”

Once you embrace Corollary #2 of Murphy’s Law (Everything takes longer than you think it will) you know you should never have mulch dumped in front of the garage door unless you’re willing to park on the street for days and even weeks. Recently I reacquainted myself with Bloch’s collection, in Murphy’s Law: The 26th Anniversary Edition (Penguin Group, 2003). I saw that although I recognized the proofs of Murphy’s Law I’d been cultivating, many other dictums in that book were also well established in my gardens. It made me laugh—which is a good thing to do on a day when Murphy’s Law pops up in your garden.

Once you embrace Corollary #2 of Murphy’s Law (Everything takes longer than you think it will) you know you should never have mulch dumped in front of the garage door unless you’re willing to park on the street for days and even weeks. Recently I reacquainted myself with Bloch’s collection, in Murphy’s Law: The 26th Anniversary Edition (Penguin Group, 2003). I saw that although I recognized the proofs of Murphy’s Law I’d been cultivating, many other dictums in that book were also well established in my gardens. It made me laugh—which is a good thing to do on a day when Murphy’s Law pops up in your garden.

Despite the aggravation they can cause, there’s much to be learned from Murphy’s Law situations. Here’s a redtwig dogwood we dug from the bed that had been first covered with rock and then, when that mulch became unsightly, buried under a second layer of plastic and rock. If I hadn’t seen it I wouldn’t have imagined what tenacity a shrub can have. This one was growing a whole new root system above its original root ball. The lower roots were atrophying, oxygen starved at the unnatural depth. The new roots were more lively, growing into the organic debris that had accumulated in the uppermost layer of rock. Here are some of those rules and observations from Bloch’s compilation, with examples of where I’ve found them lurking in the garden. Perhaps given these connections, you won’t feel frustrated or critical of yourself the next time you encounter such circumstances. You can shrug off the effects and join me in saying, “Ah well, there’s nothing to be done. It’s all Murphy’s Law!”

Despite the aggravation they can cause, there’s much to be learned from Murphy’s Law situations. Here’s a redtwig dogwood we dug from the bed that had been first covered with rock and then, when that mulch became unsightly, buried under a second layer of plastic and rock. If I hadn’t seen it I wouldn’t have imagined what tenacity a shrub can have. This one was growing a whole new root system above its original root ball. The lower roots were atrophying, oxygen starved at the unnatural depth. The new roots were more lively, growing into the organic debris that had accumulated in the uppermost layer of rock. Here are some of those rules and observations from Bloch’s compilation, with examples of where I’ve found them lurking in the garden. Perhaps given these connections, you won’t feel frustrated or critical of yourself the next time you encounter such circumstances. You can shrug off the effects and join me in saying, “Ah well, there’s nothing to be done. It’s all Murphy’s Law!”

Murphy’s Law and its first three corollaries

The Law: If anything can go wrong, it will. Its first corollary: Nothing is as easy as it looks.

One busy spring, I agreed to re-do a condominium entrance bed. It seemed a straightforward job—remove a layer of misbegotten egg rock and plastic, improve the soil and then plant flowers.

Various earlier projects ran long, pushing this make-over into Memorial Day weekend. Hoping to finish the work yet still have a bit of holiday time, we arrived at dawn to begin.

Murphy got there first. We saw the proof after we removed two truckloads of rock and peeled back the underlying plastic. Lying there was Corollary #1 in the form of an additional layer of egg rock and plastic.

Which simultaneously proved Corollary #2: Everything takes longer than you think it will. This bed renovation was going to go way over estimate.

With elegant simplicity, the situation moved right along to Corollary #3: Whenever you set out to do something, something else must be done first. What that meant in this case was that because the landfill closed early on holiday weekends, anything dug after noon this day was going to remain in my truck to complicate the beginning of my next project.

One of the worst things man can do to a tree is to stack mulch against the trunk. Moisture build-up and fungus join forces to rot the bark and destroy first the bark and then the vital cambium layer, maiming or killing the tree. The effect is the same whether that tree is a sapling or a forest giant. So why do we do it? Because someone working in a public place did it and others followed suit!New solution—new problem

One of the worst things man can do to a tree is to stack mulch against the trunk. Moisture build-up and fungus join forces to rot the bark and destroy first the bark and then the vital cambium layer, maiming or killing the tree. The effect is the same whether that tree is a sapling or a forest giant. So why do we do it? Because someone working in a public place did it and others followed suit!New solution—new problem

Sometimes proofs take longer to develop. Such was the case the first time I recognized the garden variety of Corollary #4: Every solution breeds new problems.

It began one fall when I decided to repel bulb-digging squirrels with predator urine. At the garden center I considered my choices—fox, coyote or bobcat urine. Knowing there was a fox that visited the target area regularly, it seemed unlikely the local squirrels would find fox scent repulsive. At the other end of the scale, bobcat urine seemed like overkill. Thus I bought and used the coyote product.

That night, strange warbling noises woke the owners of those urine-marked gardens. Through the window they saw the fox, pacing back and forth along the marked beds, keening and yodeling.

For years we watched squirrels like this dig and eat our bulbs. Yet what we did to solve that problem led to greater headaches, proving the statement: Every solution breeds new problems (Murphy’s Law Corollary #4).Curious about the fox’s behavior, I cracked my books and came across reports that foxes will not share territory with coyotes. No wonder our fox was upset. He thought a coyote had moved in.

For years we watched squirrels like this dig and eat our bulbs. Yet what we did to solve that problem led to greater headaches, proving the statement: Every solution breeds new problems (Murphy’s Law Corollary #4).Curious about the fox’s behavior, I cracked my books and came across reports that foxes will not share territory with coyotes. No wonder our fox was upset. He thought a coyote had moved in.

The true level of upset wasn’t apparent until late the next summer. Then, I’d been dealing with two first-ever situations for that garden—a plague of voles and an influx of rabbits. As I baited a live trap for rabbit, I mused “Why now?”

An answer leapt full blown into my head, the sum of a year’s worth of not-seeing.

“Have you seen the fox at all this year?” I began asking everyone who watched that garden. As more voices tolled the negative, my conviction grew more firm: With that bulb-protecting coyote urine we had repelled our resident rodent- and rabbit-control agent.

Not nice to fool Mother Nature

I thought I’d learned all I needed to learn from this episode but another lesson remained. Slow to germinate but full of certainty, Corollary #5 of Murphy’s Law completed the picture: Mother Nature is a bitch.

Snider’s Law: Nothing can be done in one trip.When a new fox finally filled our vacancy several years later, we called all the neighbors to come see his tracks across a late spring snow. Maybe if we hadn’t shared the news the good feeling would have lasted longer. But just a few weeks later the reports began to add up. This new fox was one that preferred raiding garbage cans to earning an honest living nabbing voles and rabbits.

Snider’s Law: Nothing can be done in one trip.When a new fox finally filled our vacancy several years later, we called all the neighbors to come see his tracks across a late spring snow. Maybe if we hadn’t shared the news the good feeling would have lasted longer. But just a few weeks later the reports began to add up. This new fox was one that preferred raiding garbage cans to earning an honest living nabbing voles and rabbits.

An assortment of other laws and their gardening proofs

Let’s see if you can smile too, about what goes wrong in your garden. Think about these other laws, precepts and axioms as they relate to garden snafus.

Leahy’s Law states: If something is done wrong often enough, it becomes right. This is the complete and only explanation for volcano mulching.

Sodd’s Second Law is: Sooner or later, the worst possible set of circumstances is bound to occur. Sodd grins “Gotcha!” when you find yourself volunteered to a committee to landscape the church front entry and the majority of the other volunteers have never grown anything except opinions. And when you learn the soil in the entry area is not only brick hard but full of buried wires and pipes. And the budget for plants is suitable only for seeds. And the pastor informs you that the Sunday School classes should be allowed to help in planting.

Those who know and heed the “Unspeakable Law” know that saying, “Aren’t those hawthorn berries gorgeous? I hope they last the winter!” is to invite a flock of cedar waxwings to descend and strip the tree the next day.Consider Commoner’s Law of Ecology: Nothing ever goes away. This is not just law but religion among members of the species Canada thistle, scouring rush and bindweed.

Those who know and heed the “Unspeakable Law” know that saying, “Aren’t those hawthorn berries gorgeous? I hope they last the winter!” is to invite a flock of cedar waxwings to descend and strip the tree the next day.Consider Commoner’s Law of Ecology: Nothing ever goes away. This is not just law but religion among members of the species Canada thistle, scouring rush and bindweed.

Help yourself by helping others recognize the Unspeakable Law: As soon as you mention something, if it’s good, it goes away. If it’s bad, it happens. Watch and listen for this before your next backyard party. Keep a gag at hand, ready for use when an uninitiated person looks out over your garden and unwittingly begins the charm that calls this law into play, “Oh, how pretty! People will love those tall blue flowers! I hope it doesn’t rain.”

At work one day measuring a property for design, I stumbled upon a haphazard jumble of pots in a shrub-choked ravine. These pots still contained potting soil, still sported tags bearing the names of desirable exotics, and in some cases still held plant remnants. Peering up toward the house through bramble branches I saw this pile was an easy sidearm toss away from the deck and recognized its existence as proof of Fahnstock’s rule for failure: If at first you don’t succeed, destroy all evidence that you tried.

Likewise, those in the know are ready to shush the person who looks at your perfectly matched and says, “Oh, those look great together. You’re so lucky you don’t have rabbits and groundhogs eating your asters like I do.” Irene’s Law is: There is no right way to do the wrong thing. It’s so simple that any transgressions can be dumbfounding. Such was the case when a man who had sold his house to my friend Sue returned the next year at “just the right time” to give her a pruning lesson. His intent: to be sure she knew the right way to prune the flowering dogwood to maintain its perfectly round lollipop figure.

Likewise, those in the know are ready to shush the person who looks at your perfectly matched and says, “Oh, those look great together. You’re so lucky you don’t have rabbits and groundhogs eating your asters like I do.” Irene’s Law is: There is no right way to do the wrong thing. It’s so simple that any transgressions can be dumbfounding. Such was the case when a man who had sold his house to my friend Sue returned the next year at “just the right time” to give her a pruning lesson. His intent: to be sure she knew the right way to prune the flowering dogwood to maintain its perfectly round lollipop figure.

Cooke’s Law (It is always hard to notice what isn’t there) is actually pretty handy: I’ve seen it employed when two parties have joint ownership of an overplanted landscape or crowded woodlot. One party embraces the premise “something has to go” while the other stands on vague principle in objection to any removals. If the party in favor of reduction recognizes the applicability of this law, he or she might look for an opportunity in the form of the other party’s next business trip or out-of-town retreat. Should tree cutters or landscapers come then, it may be months before the objector even notices any change.

Philo’s Law has comforted me when I find myself dealing with people who don’t “get it.” It is: To learn from your mistakes you must first realize that you are making mistakes. Most recently, it came to mind as I exchanged emails with a gardener who had asked, “What can I use to get rid of powdery mildew? I’ve lived here about twelve years. I spray the garden every week with an insecticide-fungicide-fertilizer mix, but I can’t seem to beat the mildew.”

Sidebar: Rainy day reading

- Ready to solo as a lawyer of Murphology? On a day when it rains and you’re a bit of weary of plant catalogs, resurrect this magazine. Find your own examples of these last few laws in your garden, and smile.

- Barber’s Rule: Anything worth doing is worth doing to excess.

- Snider’s Law: Nothing can be done in one trip.

- Ducharme’s Precept: Opportunity always knocks at the least opportune moment.

- Jong’s Law: Advice is what we ask for when we already know the answer but wish we didn’t.

- The Principle of Design Inertia: Any change looks terrible at first.

- Beach’s Law: No two identical parts are alike.

- Imbesi’s Law of the Conservation of Filth: In order for something to become clean, something else must become dirty.

- Milliken’s Maxim: Insanity is doing the same thing the same way and expecting different results.

- Melnick’s Law: If at first you do succeed, try not to look too astonished.

- Groya’s Law of Epistemology: What we learn after we know it all is what counts.

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet in her newsletter available by writing to WhatsComingUp@gmail.com.