dailyinfographic.comdailyinfographic.com:

dailyinfographic.comdailyinfographic.com:

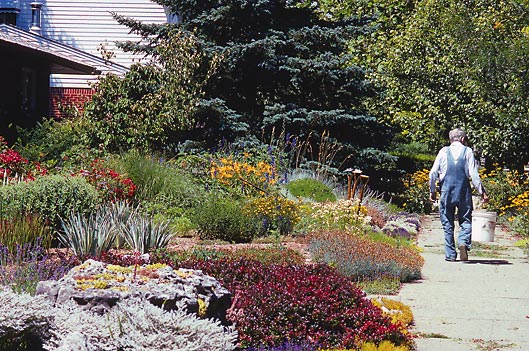

Today I was making a sandwich for lunch, I scoured my fridge for tomatoes but none were around. I did some quick thinking, walked out back and plucked a tomato. No trip to the store, no unwanted chemicals, no cash exchanged hands, but I still got a slick of tomato on my sandwich. That story isn’t true, but it could be for very little cost and everyone knows nothing beats a fresh tomato.